|

Gay Wisdom for Daily Living brought to you by White Crane Institute ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

|

|

||||

| This Day in Gay History | ||||

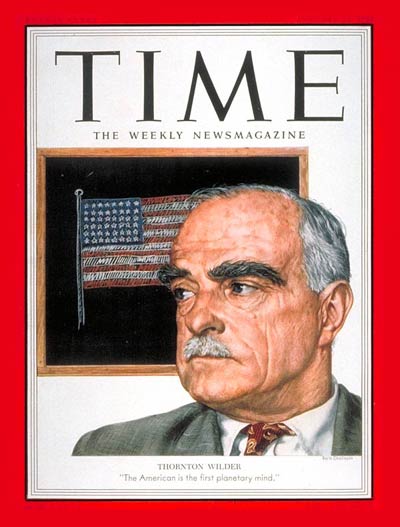

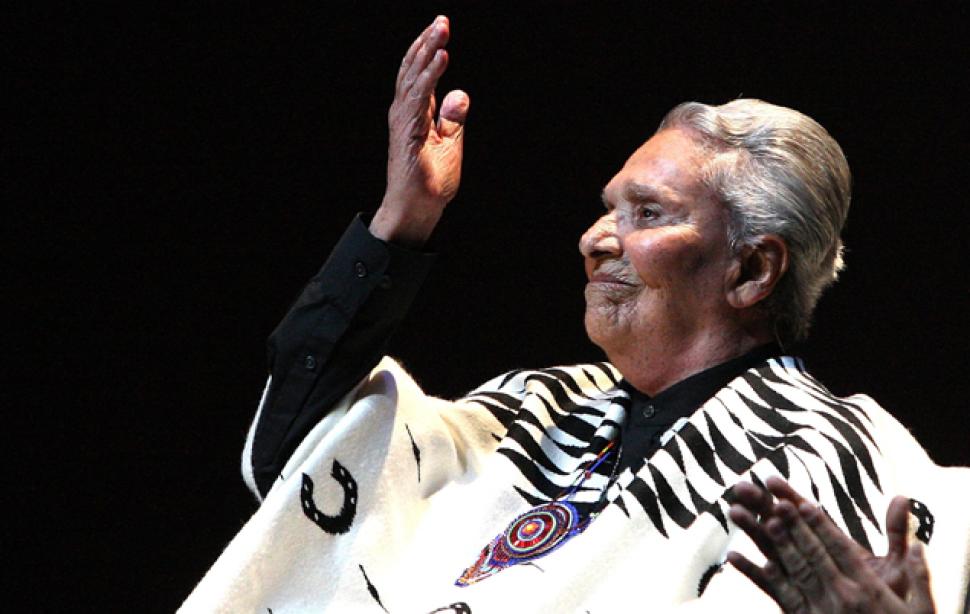

April 17Born  The Next Table C. P. Cavafy, 1863 – 1933 He can’t be more than twenty-two. And yet I’m certain it was at least that many years ago that I enjoyed the very same body. This isn’t some erotic fantasy. I’ve only just come into the casino and there hasn’t been time enough to drink. I tell you, that’s the very same body I once enjoyed. And if I can’t recall precisely where—that means nothing. Now that he’s sitting there at the next table, I recognize each of his movements—and beneath his clothes I see those beloved, naked limbs again. The Next Table C. P. Cavafy, 1863 – 1933 He can’t be more than twenty-two. And yet I’m certain it was at least that many years ago that I enjoyed the very same body. This isn’t some erotic fantasy. I’ve only just come into the casino and there hasn’t been time enough to drink. I tell you, that’s the very same body I once enjoyed. And if I can’t recall precisely where—that means nothing. Now that he’s sitting there at the next table, I recognize each of his movements—and beneath his clothes I see those beloved, naked limbs again.1863 - CONSTANTINE P. CAVAFY, Greek poet born (d. 1933); During his lifetime Cavafy was considered the poet of Alexandria, and today his name, for those who don’t know his poetry is identified primarily with Lawrence Durrell’s characterizations of him in the Alexandria Quartet. Few know, however, that E.M. Forster was responsible for introducing Cavafy to English-speaking readers, for acting as the poet’s unpaid agent, and for promoting his reputation. In return, Cavafy doubted that his mousy benefactor even knew what his poems were about. He was wrong, and others were quick to find out, as well. As Marguerite Yourcenar, his French translator has remarked: “Cavafy’s poems are like near Eastern cafes – you never see a woman in them.” The American poet Mark Doty’s book My Alexandria uses the place and imagery of Cavafy to create a comparable contemporary landscape. W.H. Auden wrote: “Ever since I was first introduced to his poetry by the late Professor R.M. Dawkins over thirty years ago, C.P. Cavafy has remained an influence on my own writing; that is to say, I can think of poems which, if Cavafy were unknown to me, I should have written quite differently or perhaps not written at all. Yet I do not know a word of Modern Greek, so that my only access to Cavafy’s poetry has been through English and French translations. This perplexes and a little disturbs me. Like everybody else, I think, who writes poetry, I have always believed the essential difference between prose and poetry to be that prose can be translated into another tongue but poetry cannot. But if it is possible to be poetically influenced by work which one can read only in translation, this belief must be qualified. There must be some elements in poetry which are separable from their original verbal expression and some which are inseparable. It is obvious, for example, that any association of ideas created by homophones is restricted to the language in which these homophones occur. Only in German does Welt rhyme with Geld, and only in English is Hilaire Belloc’s pun possible. When I am dead, I hope it may be said: ‘His sins were scarlet, but his books were read’. 1897 - THORNTON WILDER, American dramatist (d. 1975); Nowadays, you’re supposed to be decidedly middle-brow if you get wet-eyed at the concluding scenes of Our Town. Well, hell, who wants to be high-brow anyway?! So admit it, the end of that play really gets you every time doesn’t it? (Well, almost every time. When June Allyson attempted to play the lead many years ago, the perverse among us cheered when Emily died in childbirth.) When you think of that famous closing scene, with its umbrellas and the folding chairs on which the dead of "Grovers Corners" sit, think of Samuel M Steward (see July 23) who, when Wilder was having difficulties finishing his play, accompanied the playwright on a long, long walk in the rain. The next day, Wilder completed his play. Steward later quipped, "Wilder was a superb craftsman, but now that his homosexuality has been officially recognized, his reputation is almost certain to slip. As we all know, queers don’t know how to write plays." Wilder’s Our Town, set in fictional Grover's Corners, New Hampshire was inspired by his friend Gertrude Stein's novel The Making of Americans, and many elements of Stein's deconstructive style can be found throughout the work. Our Town employs a choric narrator called the “Stage Manager” and a minimalist set to underscore the universality of human experience. (Wilder himself played the Stage Manager on Broadway for two weeks and later in summer stock productions.) Following the daily lives of the Gibbs and Webb families as well as the other inhabitants of Grover’s Corners, Wilder illustrates the importance of the universality of the simple, yet meaningful lives of all people in the world in order to demonstrate the value of appreciating life. The play won the 1938 Pulitzer Prize. That same year Max Reinhardt directed a Broadway production of The Merchant of Yonkers, which Wilder had adapted from Austrian playwright Johann Nestroy's Einen Jux will er sich machen (1842). It was a failure, closing after just 39 performances. 1919 - ISABEL VARGAS LIZANO (d: 2012), better known as CHAVELA VARGAS, was a Costa Rican-born Mexican singer. She was especially known for her rendition of Mexican rancheras, but she is also recognized for her contribution to other genres of popular Latin American music. She has been an influential interpreter in the Americas and Europe, muse to figures such as Pedro Almodovar, hailed for her haunting performances, and called "la voz áspera de la ternura", the rough voice of tenderness. She is featured in many Almodóvar's films, including La Flor de mi Secreto in both song and video. She has said, however, that acting is not her ambition, although she had previously participated in films such as 1967's La Soldadera. Vargas recently appeared in the 2002 Julie Taymor film Frida, singing "La Llorona" (The Weeping Woman). Her classic "Paloma Negra" (Black Dove) was also included in the soundtrack of the film. Vargas herself, as a young woman, was alleged to have had an affair with Frida Kahlo, during Kahlo's marriage to muralist Diego Rivera. She also appeared in Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu's Babel, singing "Tú me acostumbraste" (You Got Me Used To), a bolero of Frank Dominguez. Joaquin Sabina’s song "Por el Boulevar de los Sueños Rotos" ("Down the Boulevard of Broken Dreams") is dedicated to Vargas. Her heavy drinking and raucous life took their toll, and she vanished from public life in the 1970s. Submerged in an alcoholic haze, she said, she was taken in by an Indian family who nursed her back to health without knowing who she was. In 2003, she told The New York Times that she had not had a drink in twenty-five years. In the early 1990s she began singing again at El Habito, the bohemian Mexico City nightclub. From there her career took off again, with performances in Latin America, Europe and the United States. At 81, she announced that she was a lesbian. “Nobody taught me to be like this,” she told the Spanish newspaper El País in 2000. “I was born this way. Since I opened my eyes to the world, I have never slept with a man. Never. Just imagine what purity. I have nothing to be ashamed of.” On the eve of her Carnegie Hall debut in 2003, she looked back on how her singing had changed over her career. “The years take you to a different feeling than when you were 30,” she said in an interview with The Times. “I feel differently, I interpret differently, more toward the mystical.” Instead of holding a traditional Mexican wake, friends, fans and musicians gathered on Monday evening for a musical tribute at Plaza Garibaldi in Mexico City, where Ms. Vargas had spent many a night drinking with Mr. Jiménez. | ||||

|

|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8| Gay Wisdom for Daily Living from White Crane Institute "With the increasing commodification of gay news, views, and culture by powerful corporate interests, having a strong independent voice in our community is all the more important. White Crane is one of the last brave standouts in this bland new world... a triumph over the looming mediocrity of the mainstream Gay world." - Mark Thompson Exploring Gay Wisdom & Culture since 1989! |8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8|O|8| | ||||

|

|||||

|