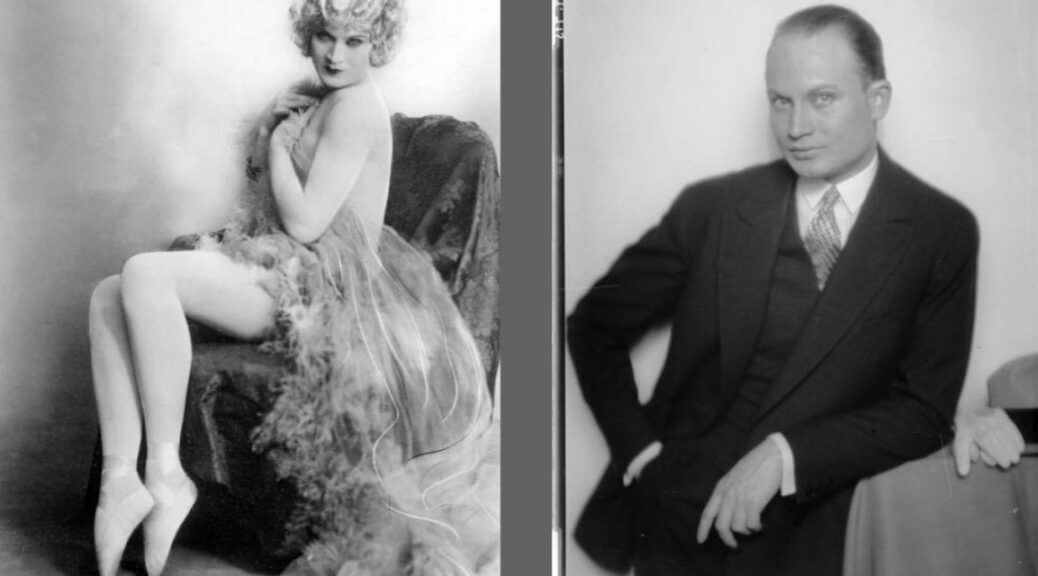

BARBETTE (born Vander Clyde) born (d. 1973); Born in Round Rock, Texas, Clyde achieved international fame as Barbette, a female impersonator and trapeze and high-wire performer.

Enamored of the circus after his mother took him to his first performance in Austin, Clyde began practicing on the clothesline in his mother’s yard and working in the fields for money to go to as many circuses as possible. After graduating from high school at age fourteen, he traveled to San Antonio to answer a Billboard advertisement placed by one of the Alfaretta Sisters, “World Famous Aerial Queens.” He joined the act on the condition that he dress as a girl, since his partner believed that women’s clothes made a wire act more dramatic. He later performed in Erford’s Whirling Sensation, in which he and two others hung by their teeth from a revolving apparatus.

If you’ve seen the idiotic Victor/Victoria and wondered what all the fuss was about when Julie Andrews, looking very much like Julie Andrews, sings and dances in female attire and then, as the audience goes crazy, removes her wig and reveals herself to be a man, who still looks very much like Julie Andrews, it was Barbette whom she was supposed to be impersonating.

During this period Clyde began developing a solo act in which he appeared and performed as a woman and removed his wig to reveal his masculinity at the end of the performance. After adopting the name Barbette, he traveled throughout the United States performing the act, which became wildly popular. In the fall of 1923 the William Morris Agency sent him to England and then to Paris, where he opened at the Alhambra Music Hall. Barbette became the talk of Paris and was befriended by members of both American café society and French literary and social circles.

In particular, his artistry was championed by French poet and dramatist Jean Cocteau. Inspired by Barbette’s act, which he described as “an extraordinary lesson in theatrical professionalism,” Cocteau wrote a review in the July 1926 issue of the Nouvelle Revue Française, “Le Numéro Barbette,” which is considered a classic essay on the nature of art. As described by Cocteau, Barbette’s acrobatics became a vehicle for theatrical illusion.

From his entrance, when he appeared in an elaborate ball gown and an ostrich-feather hat, to an elaborate striptease down to tights and leotard in the middle of the act, Barbette enacted a feminine allure that was maintained despite the vigorous muscular activity required by his trapeze routine.

Only at the end of the performance, when he removed his wig, did he dispel the illusion, at which time he mugged and flexed in a masculine manner to emphasize the success of his earlier deception. To Cocteau, Barbette’s craftsmanship, practiced on the fine edge of danger, elevated a rather dubious stunt to the level of art, analogous to the struggle of a poet.

Cocteau wrote about Barbette on several other occasions, and in 1930 he used the aerialist in his first film, Le Sang d’un Poete (Blood of a Poet), in which the bejeweled and Chanel-clad Barbette and other aristocrats applauded a card game that ends in suicide.