Portrait of An Artist as Zen Monk

Portrait of An Artist as Zen Monk

Victor Marsh Interviews Don Bachardy

On Art, the Transcendent and Christopher Isherwood

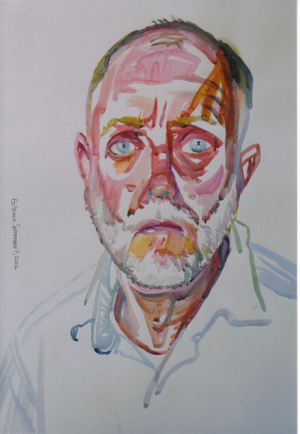

[Editor’s Note: The artwork on this page is by Don Bachardy. We gratefully acknowledge Bachardy’s allowing us to display his beautiful work with this excerpt and within the pages of this issue of White Crane.]

“Work for the work itself, not the fruits thereof.” Vedantic teaching cited by Don Bachardy in Stars in My Eyes

Technically artist Don Bachardy (and His Kind, if you will) wouldn’t be called ‘beat’ or ‘bohemian’ — his life has been far too glamorous. A fine artist his entire life, Don Bachardy will forever be identified with novelist and diarist Christopher Isherwood, who discovered him on a Santa Monica beach in 1953 when Don was 18 years old, and became his patron and lover for life.

Isherwood encouraged Bachardy’s significant talents and opened golden doors for him at a time of iconic “glitterati” in Hollywood, sharing a life in the company of legends — Garbo & Maugham, Auden & Spender, Gerald Heard, Krishnamurti & Swami Prabhavananda — to skim just the shining surface of their circle. In his Diaries, Isherwood wrote of Bachardy:

“I feel a special kind of love for Don…at a very deep level, beneath names for things or their appearances… There’s a brilliant wide-openness about his mouse face with its brown eyes and tooth gap and bristling crew cut, which affects everyone who sees him. If one could still be like that at forty, one would be a saint.”

Isherwood went on, years later:

“What shall I write about Don, after seven years? Only this — he has mattered and does matter more than any of the others. Because he imposes himself more, demands more, cares more — about everything he does and encounters. He is so desperately alive.”

In his early 70s now, Bachardy went on to paint portraits of well-known and diverse subjects such as Myrna Loy, Ginger Rogers, Anaïs Nin, Gore Vidal, Jane Fonda, Katharine Hepburn, James Merrill, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Mapplethorpe, Aldous Huxley, and many others.

In the late 1980s Bachardy created portraits of a dozen gay rights leaders: Elaine Noble, Frank Kameny, Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, Morris Kight, Charles Bryden, James Foster, Bruce Voeller, David B. Goodstein, Jean O’Leary, Rev. Troy Perry, and Barbara Gittings. In 1995, the series was donated to the Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell University Library. Bachardy recently painted life partners, Gay Spirit author Mark Thompson and the Rev. Canon Malcolm Boyd. His drawings and paintings are included in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the M.H. de Young Museum of Art (SF), the University of Texas, Henry E. Huntington Library & Art Gallery, San Marino, California, the University of California at Los Angeles, the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University, Princeton University, the California State Capitol Building (the official portrait of Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr.), the Smithsonian and the National Portrait Gallery in London.

In the late 1980s Bachardy created portraits of a dozen gay rights leaders: Elaine Noble, Frank Kameny, Phyllis Lyon, Del Martin, Morris Kight, Charles Bryden, James Foster, Bruce Voeller, David B. Goodstein, Jean O’Leary, Rev. Troy Perry, and Barbara Gittings. In 1995, the series was donated to the Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell University Library. Bachardy recently painted life partners, Gay Spirit author Mark Thompson and the Rev. Canon Malcolm Boyd. His drawings and paintings are included in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the M.H. de Young Museum of Art (SF), the University of Texas, Henry E. Huntington Library & Art Gallery, San Marino, California, the University of California at Los Angeles, the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University, Princeton University, the California State Capitol Building (the official portrait of Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr.), the Smithsonian and the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Last year Isherwood scholar and White Crane contributor Victor Marsh visited with Bachardy in the home he and Isherwood shared in Santa Monica.

Don Bachardy’s house sits alone on a small promontory, with great views across a canyon towards the Palisades and left down to the beach and the ocean. It’s a balmy spring-like day (even though it’s early January) and the air over the Santa Monica canyon is crisp and clear this morning.

Bachardy is short-statured and resolutely slim. He’s dressed in blue tones: crisp blue jeans without belt and a short-sleeved grey-blue cotton T-shirt. Grey/white hair, cut short, although longer on top, where it stands up like a longish crew cut. His glasses are a narrow, modern, rimless strip, with dark green side bars.

Bachardy is short-statured and resolutely slim. He’s dressed in blue tones: crisp blue jeans without belt and a short-sleeved grey-blue cotton T-shirt. Grey/white hair, cut short, although longer on top, where it stands up like a longish crew cut. His glasses are a narrow, modern, rimless strip, with dark green side bars.

He tends to look away while speaking, sometimes even sinking his head into his chest as if he were thinking deeply; but when he lifts his head and looks you directly in the face, the effect is remarkable. It is as though he is reserving his direct gaze for “special effect.” The lenses of his glasses give his eyes great depth of field and enlarge the gaze, which reinforces the impact. I recognize the intensity of the gaze from the self-portrait used at the Huntington exhibition.

He is very articulate and sometimes pauses, mid-sentence, searching for the right word, which invariably comes up apt. His voice is light in tone but emphatic, with a slightly hesitant delivery. The accent is mid-Atlantic and precise. No hint of a California drawl. He is remarkably respectful and attentive, listening carefully to what you say and he doesn’t interrupt, always giving you time to finish what you are saying. One feels drawn to reciprocate.

Everything about his manner, his personal style and presentation suggest a man with a great deal of self-discipline, who doesn’t often take the easy way; most alive when he is setting himself challenges. He is as sharp as a razor, yet not at all abrasive, with a great deal of the Isherwood-esque charm, judiciously disbursed. There’s refinement without fuss, a well-honed sensibility and a respectful reserve, rather than gush. A tight economy in his physical manner and communication, nothing extraneous, to me indicates a Zen-like personal esthetic. You feel like he doesn’t waste time. He works every day and even in his very early 70s, you get the feeling that he’ll be working for many years to come.

The house is single story, with rooms lined up along the same rectangular axis. The front door opens into a white living room with large windows looking out across the Canyon. Every available inch of wall space is hung with artwork.

We begin by discussing Peter Parker’s recent Isherwood biography. Bachardy says he has resisted criticizing the book until now because he didn’t want to draw any further attention to it and boost its sales.

Victor Marsh: You said that Parker came here and you gave him access to materials that otherwise…

Victor Marsh: You said that Parker came here and you gave him access to materials that otherwise…

Don Bachardy: To everything, yes. Papers, photographs, letters, diaries, the works; and he was living in the house here. He came on two separate occasions and on the second one, the young man I was living with, Tim Hilton said: Either he goes, or I go. And I had to tell Parker that he must go to a motel or hotel…

Marsh: The Times of London printed a very brief news item saying they had called you and reported that you weren’t happy with the biography.

Bachardy: I was very careful what I said. I didn’t say anything substantial. I suppose my very coolness was interpreted as disapproval.

Marsh: Did you find it an unsympathetic portrayal of Isherwood?

Bachardy: Yes, I did. He really puts down Chris continually, and wags his finger and makes fun of him, like a schoolmarm. He’s so superior! Who is he, you know; who is he? That same old tired British attitude: that Isherwood never wrote anything nearly as good as his work in England once he came to this country.

Marsh: He does give the second half of the life equal space in the book; he spends the first half…

Bachardy: But it’s all telescoped, it’s not nearly as detailed.

Marsh: He says in the interview he did with The Telegraph that he doesn’t wag his finger over aspects of Isherwood’s behavior that he might have disapproved of…

Bachardy: If he’s got more complaints about Isherwood, um, the book would be overwhelmingly negative! You mean, he held back? That makes it absolutely a total lie…when he said to me…when he interviewed for the job, he told me a lie. Really there’s hardly any praise for Chris in the whole book. I read it very carefully.

Marsh: You said that you feel betrayed?

Bachardy: Yes, yes, totally. Wouldn’t you feel betrayed — somebody tells you he admires a writer and then writes a biography like this? And it’s personally critical as well as critical of the work. I just wonder what Olympic mountain he is descending from?

Marsh: I wrote a short review of the book in which I said that even if he tried to practice restraint in “wagging his finger” over Isherwood’s behavior, that he didn’t exercise the same restraint in regard to the Swami. As reviews of the book have appeared around the world, people have taken that very conventional attitude towards Swami ji that Parker sets up in the book in which he presents him as sly, manipulative and cunning, interested only in Isherwood’s cachet as a writer for the sake of the Vedanta Society. He uses legalistic language and even claims that he was not really sympathetic to homosexuals; that he was giving Isherwood special treatment, which I think is a lot of tommyrot. I don’t see how anyone with Isherwood’s insight into character could be so duped by somebody for 40 years.

Bachardy: Well, exactly. Yes, forty years of really close relationship, observing this man, often on a daily basis, when he was living in the Vedanta Center. Chris, with all of his intuitive range, could be fooled by the kind of character Parker describes.

Bachardy: Well, exactly. Yes, forty years of really close relationship, observing this man, often on a daily basis, when he was living in the Vedanta Center. Chris, with all of his intuitive range, could be fooled by the kind of character Parker describes.

Marsh: He ends that section by saying of course “this is not to mean that Isherwood wasn’t duped in any way.” With that lame disclaimer, why the gratuitous attack? I feel that it’s because of the typical British colonial attitude towards the belief systems and spirituality of subject races.

Bachardy: Yes, exactly. That attitude towards Chris’s involvement with Vedanta and the attitude of Chris’s falling apart and becoming a mediocre writer once he came to this state. It’s all that British attitude… I feel that I couldn’t have chosen a worse person for the biography.

Marsh: Well it seems to be such an authoritative book because it’s so long, but size isn’t everything! He gets tons of detail — the historical detail — in place: “he went here, he met that person, he did this and that”…

Bachardy: But he’s more interested in Kathleen (the mother) and Richard (the brother) than in Chris; he really liked them better, it’s perfectly clear. And he would say so, he was so fascinated by them, and that was years ago. Over the years since he took on the job, my faith in him was diminishing rapidly, until finally there was really very little there. But even so, when I read the book, I was really stunned.

Marsh: He has been praised by so many reviewers for…

Bachardy: He’s a powerful critic.

Marsh: …for recuperating Kathleen’s reputation from the shabby treatment at the hands of her favorite son; but if he hadn’t stepped away from her and everything she represented, he would have ended up like Richard, with his broken down, eccentric life, not productive of anything.

Bachardy: Well I think Kathleen, in Parker’s mind, stands for England. Not only was England insulted when Chris abandoned her, but his mother was bereft.

Marsh: John Sutherland, who’s a professor in London said…

Bachardy: Did he write the [Stephen] Spender biography?

Marsh: Yes, apparently he was rushing to get it out at the same time; Parker seems to pride himself on spending twelve years on his biography, by way of contrast.

Marsh: Yes, apparently he was rushing to get it out at the same time; Parker seems to pride himself on spending twelve years on his biography, by way of contrast.

Bachardy: He came here to interview me and I rather liked him and weirdly enough, I thought he was rather like Stephen himself.

Marsh: He said in his review of this biography that Isherwood had made “a late life conversion to transcendentalism.” “Late life” when it was really barely half way through. There’s a lack of interest in the facts after he came to America…

Bachardy: Yes, they’re really not interested. Even though in terms of pages, Parker may have given as much to the Californian part of Chris’s life, what he is really interested in and what is much more vividly written is the first half. You know, he hardly asked me anything at all. And stayed in the house for two weeks; I don’t know how I stood it.

Marsh: You don’t mind if I make your displeasure known?

Bachardy: I’m still hesitant for fear…You know, people who have heard of me will say, “Oh well if he doesn’t like it, it must be spicy” or something and it’s certainly not spicy.

Marsh: Let’s go back to the misrepresentation of Swami Prabhavananda. I think Chris was lucky to meet an independently-minded exponent of the tradition. I imagine that there would have been other swamis from the Math in Calcutta who could have been more straight-laced and that Isherwood was fortunate to find someone who was liberated from conventional attitudes.

Bachardy: Oh yes, Prabhavananda was really very unusual. The other swamis at the Belur Math were quite a different kettle of fish. Of course, the biography of Ramakrishna Chris did had to be vetted by them and they made all kinds of demands. Chris would have written a quite, quite different book about Ramakrishna if they hadn’t interfered. It was amazing that Chris published under his name, which really wasn’t entirely his work.

Bachardy: Oh yes, Prabhavananda was really very unusual. The other swamis at the Belur Math were quite a different kettle of fish. Of course, the biography of Ramakrishna Chris did had to be vetted by them and they made all kinds of demands. Chris would have written a quite, quite different book about Ramakrishna if they hadn’t interfered. It was amazing that Chris published under his name, which really wasn’t entirely his work.

Marsh: And yet it’s still very revealing. I think a lot comes through that a conventional biographer wouldn’t have really covered, like the cross-dressing and the different modes of devotion. It gives a very sympathetic picture of Vedanta and creates a basis for the acceptance of “others” because of the non-duality aspect — not just dividing the world up into male and female, the gay/straight, all the binaries get dissolved in a non-dual system. Isherwood seems to me to have had tremendous insight into it, philosophically.

Bachardy: Yes, yes! He was very intelligent!

Marsh: He was also able to get past the colonial condescension, you know, this is the religion of the Hindus; Auden called it “heathen mumbo jumbo.”

Bachardy: Well, of course, he examined and re-examined Prabhavananda under every conceivable light and weighed his actions continually. He wasn’t just overcome with awe; he was very cautious.

Marsh: And Prabhavananda passed the test!

Bachardy: Yes!

Marsh: What about your own relationship? I’ve noticed with my own guru that a dozen people can come to him and receive instruction, learn the meditation practice, but the path they take thereafter can be very different, even though the practice is similar and they all have a relationship with him as a Teacher, but each person’s path is so individual. How would you say your path differed from the way that, say, Chris followed up? Would you still call yourself a Vedantist?

Bachardy: Oh yes, I do and I still do practice, I still tell my beads, every day.

Marsh: People don’t know this about you! There was an interview you both did with Mark Thompson for Gay Spirit and Chris said, when he was asked: Do you mind speaking about your spirituality? He said the Hindus have a very good expression: If you have a spiritual experience, you had better shut up about it, as you would if your mother were a whore! Unless he felt there was a sincere interest from the other side, he wouldn’t go there. So it’s interesting that your practice continues. What was your own relationship with the Swami like?

Bachardy: I was alone with him on some occasions. He sat for me, Prabhavananda, several times. We were absolutely alone together and that in itself is a meditative experience, because you’re just sitting there for hours with nothing to do but examine the contents of your mind! So I consider that was very beneficial exposure for me.

Marsh: That was a most intense form of darshan!

Bachardy: Yes, yes, exactly and I took it as such. And I think some of the pictures I did of him are very like him.

Marsh: Did you feel that you had the same kind of bhakti, devotional, affectionate relationship with him?

Bachardy: You know, Chris was really my guru, and he was the go-between for Prabhavananda and me. Prabhavananda and I were very respectful of each other and cordial and friendly but I was very careful not to try to grab his attention. I always kept a discreet distance.

Also, I was on sufferance from the beginning because, of course, Chris, just a few months after we got to know each other, well, he took me up to meet Swami. He wasn’t going to fool around. He wasn’t going to try to hide me at home. He took me up there to meet him.

It was a little bit like meeting the parents. I knew it and Prabhavananda knew it. It had to be above board. That really established the basis for the rest of the relationship I had with Prabhavananda. That’s why I stopped going to Vedanta Place because I was hardly ever there without Chris and I didn’t want to test them, their treatment of me, after Chris was dead. I didn’t want to put them into that…because of course I would notice the slightest difference. I just didn’t want to do that to them. And besides as I said I felt that my real guru was Chris and what I got from Prabhavananda was filtered for me by Chris. Prabhavananda was long since dead by the time of Chris’s death, so there was really no point in going up to Vedanta Place.

It was a little bit like meeting the parents. I knew it and Prabhavananda knew it. It had to be above board. That really established the basis for the rest of the relationship I had with Prabhavananda. That’s why I stopped going to Vedanta Place because I was hardly ever there without Chris and I didn’t want to test them, their treatment of me, after Chris was dead. I didn’t want to put them into that…because of course I would notice the slightest difference. I just didn’t want to do that to them. And besides as I said I felt that my real guru was Chris and what I got from Prabhavananda was filtered for me by Chris. Prabhavananda was long since dead by the time of Chris’s death, so there was really no point in going up to Vedanta Place.

Marsh: But you continue the practice?

Bachardy: Yes I do.

This is just an excerpt from this issue of White Crane. In fact this is a mere fraction of this fascinating interview with Don Bachardy. But we are a reader-supported journal and need you to subscribe to keep this conversation going. So to read more from this wonderful issue SUBSCRIBE to White Crane. Thanks!