February 23

POPE PAUL II, born (d: 1471); Exceptionally vain (even for a pope) – Paul wanted to take the name “Formosus I,” i.e. "the Well-Shaped, " upon his erection, er, I mean election. Any name chosen would have been better than the one given him sarcastically by his successor, Pius II – “Maria Pietissima,” – Our Lady of Pity. Personally I'm getting Rodney Dangerfield vibes.) All of this is delicious rumor, of course, as is the story of his death of a heart attack while playing bottom to his favorite top. Popes have a lot of enemies, you know. Most of them well-earned.

GEORG FRIEDRICH HANDEL, German/British Baroque composer born (d. 1759); “Handle”...it’s correctly pronounced “handle” a friend used to cajole. Of the German composer who anglicized the spelling of his name upon removing to England, a contemporary wrote: “His social affectations were not very strong; and to this it may be imputed that he spent his whole life in a state of celibacy; that he had no female attachments of another kind may be ascribed to a better reason.” What was the “better reason” that made Handel eschew not only marriage, but “female attachments of another kind,” presumably mistresses or whores?

ROBIN WOOD, British-Canadian teacher, author, film theorist and critic, born (d: 2009); Wood was an secondary school English teacher who transformed the art of film criticism, especially through his appraisals of Howard Hawks, Arthur Penn, Ingmar Bergman, and in particular, Alfred Hitchcock. A “difficult child” he was frequently taken by the family maid to see movies to get him out of the house. This introduction to the silver screen lead to a life-long infatuation with Jean Arthur, Claudette Colbert and Cary Grant and film in general.

While teaching English, he submitted an article on Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho to the celebrated French cinema journal Cahier du Cínema. Wood championed a morally committed, ethical approach to criticism which only became more acute and pointed when he came out as a gay man in the 1970s. His writings were meant “To contribute, in however modest a way, to the possibility of social revolution, along lines suggested by radical feminism, Marxism and Gay Liberation.” The turning point in Wood's philosophical views can arguably be pinpointed in his essay Responsibilities of a Gay Film Critic, originally a speech at the National Film Theater and later printed in Film Comment magazine in 1978. It was subsequently included in the revised edition of his book Personal Views [Wayne State University Press: ISBN# 9780814332788.]

But his chief fascination, and his reputation, was Alfred Hitchcock. “A lot of people thought it was ridiculous, this idea of taking Hitchcock seriously,” he said. “He was seen simply as an entertainer; one was merely amused by his films...a few shocks, a few laughs and that was it.”

But to Wood, Hitchcock was more. “I think the best of Hitchcock films continue to fascinate me because he’s obviously right inside them, he understands so well the male drive to dominate, harass, control and at the same time he identifies strongly with the woman’s position.” Many of his students, including underground filmmaker and porn star Bruce LaBruce, have gone on to notable careers.

Wood had been married and fathered three children. Wood was Toronto University’s York professor emeritus of film. He died of complications of Leukemia and is survived by his partner, Richard Lippe.

Carol "NIECY" BETTS (formerly NASH); is an American comedian, actress, television host, model, and producer, best known for her performances on television.

Nash hosted the Style Network show Clean House from 2003 to 2010, for which she won an Emmy Award in 2010. As an actress, she played the role of "Deputy Raineesha Wlliams" in the Comedy Central comedy series Reno 911. Nash received two Primtetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series and a Critic;s' Choice Television Award for Best Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series nominations for her performance as nurse Denise "DiDi" Ortley in the HBO comedy Getting On. She also starred as Lolli Ballantine on the TV Land sitcom The Soul Man, and played Denise Hemphill in the Fox horror-comedy anthology series, Scream Queens. In 2017, she began starring as Desna Simms, a leading character, in the TNT crime comedy-drama Claws.

Nash has also played a number of roles in films and has made many guest appearances on television shows. In 2014, Nash played the role of civil rights activist Richie Jean Jackson in the historical drama film Selma directed by Ava Duvernay. In 2019, she starred as Delores Wise in the Ava DuVernay' miniseries When They See Us, for which she was nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Limited Series or Movie. In 2018, Nash received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Nash was married for 13 years to Don Nash, an ordained minister, before filing for divorce in June 2007. They have three children together. Niecy Nash became engaged to Jay Tucker in September 2010. Nash participated in a TLC reality show that followed the preparations for the wedding. Nash and Tucker were married in May 2011 in Malibu.

In October 2019, Nash announced her pending divorce from Jay Tucker via an Instagram post. The divorce was finalized on March 10, 2020. On August 31, 2020, Nash announced that she and singer Jessica Betts had married and came out as bisexual.

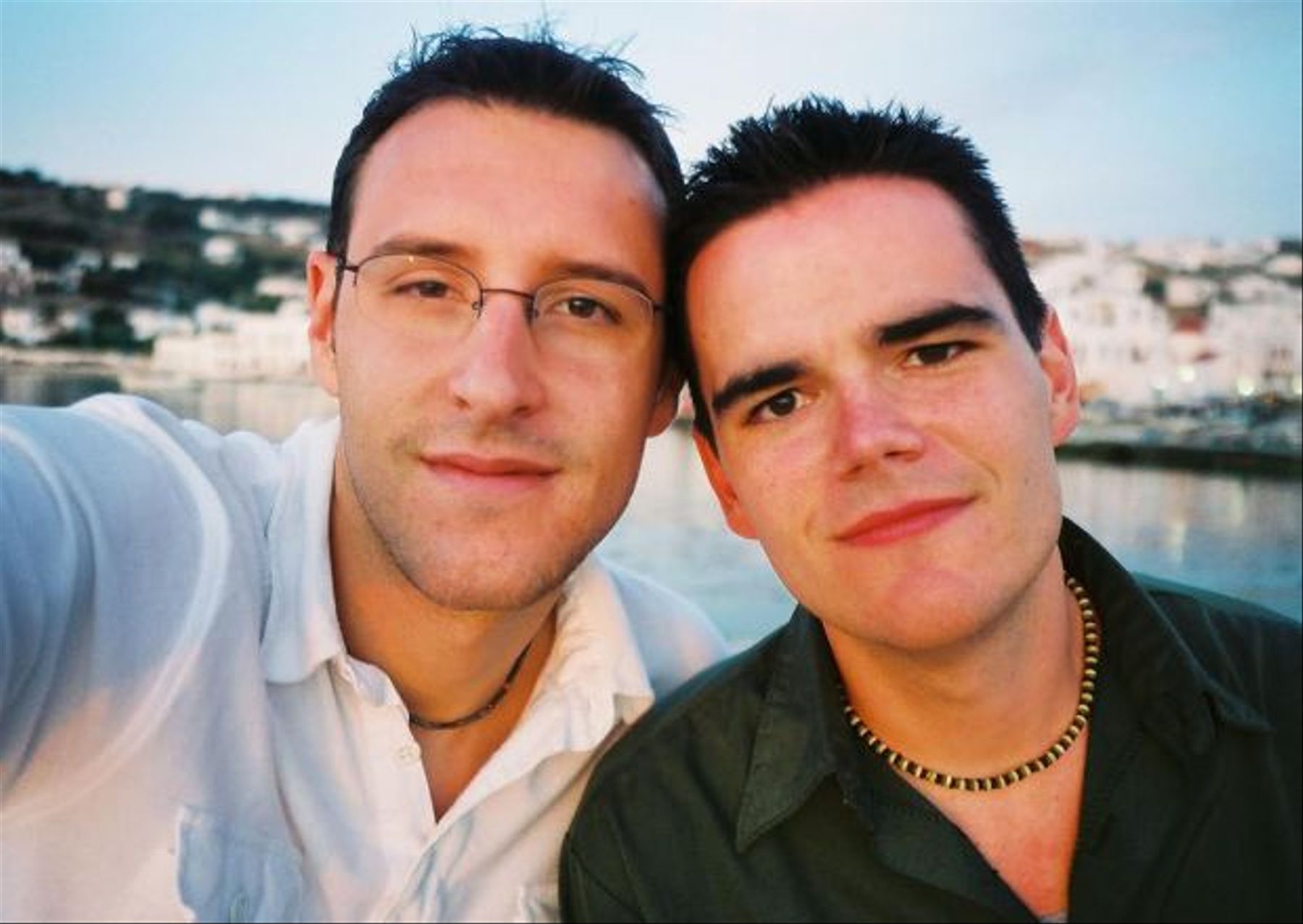

MICHAEL AUSIELLO, born on this date, is an American television industry journalist, author, and actor. He was a senior writer at TV Guide and its companion website, TVGuide.com, between 2000 and 2008. From 2008 to 2010, he wrote and reported for Entertainment Weekly before launching his own television news site, TVLine.

Ausiello was married to photographer Kit Cowan, who died of a rare form of cancer in February 2015. Ausiello chronicled the last year of Cowan's life and their 13-year relationship in a memoir in 2017, Spoiler Alert: The Hero Dies. A film based on that memoir, Spoiler Alert, was released in December 2022, starring Jim Parsons as Ausiello.

Ausiello grew up in Roselle Park, New Jersey, and attended Roselle Park High School. He is a graduate of the University of Southern California.

Ausiello contributed commentary to media outlets outside of TV Guide, such as Today, Good Morning America, Fox & Friends, American Morning, Inside Edition, Extra, Access Hollywood, and Entertainment Tonight. He is a regular guest every Friday morning on Sirius Satellite Radio's popular morning show, "OutQ in the Morning" (Channel 109) with host Larry Flick, where they converse with callers about all things television—shows, stars, and plot lines, including scoops and spoilers.

Having become friends with actors and producers such as Amy Sherman-Palladino, Ausiello has appeared in a few cameo roles on episodes of television series including Gilmore Girls, Veronica Mars, and Scrubs.

The traditional date for the publication of the GUTENBERG BIBLE, the first Western book printed from movable type thus transforming what had been an apocryphal transcription and imprecise oral tradition into rigid stone.

While the Gutenberg Bible helped introduce printing to the West, the process was already well established in other parts of the world. Chinese artisans were pressing ink onto paper as early as the second century A.D., and by the 800s, they had produced full-length books using wooden block printing. Movable type also first surfaced in the Far East. Sometime around the mid-11th century, a Chinese alchemist named Pi Sheng developed a system of individual character types made from a mixture of baked clay and glue. Metal movable type was later used in Korea to create the “Jikji,” a collection of Zen Buddhist teachings. The Jikji was first published in 1377, some 75 years before Johannes Gutenberg began churning out his Bibles in Mainz, Germany.

By studying the size of Gutenberg’s paper supply, historians have estimated that he produced around 180 copies of his Bible during the early 1450s. That may seem miniscule, but at the time there were probably only around 30,000 books in all of Europe. The splash that Gutenberg’s Bibles made is evident in a letter the future Pope Pius II wrote to Cardinal Carvajal in Rome. In it, he raves that the Bibles are “exceedingly clean and correct in their script, and without error, such as Your Excellency could read effortlessly without glasses.”

Most Gutenberg Bibles contained 1,286 pages bound in two volumes, yet almost no two are exactly alike. Of the 180 copies, some 135 were printed on paper, while the rest were made using vellum, a parchment made from calfskin. Due to the volumes’ considerable heft, it has been estimated that some 170 calfskins were needed to produce just one Gutenberg Bible from vellum.

Out of some 180 original printed copies of the Gutenberg Bible, 49 still exist in library, university and museum collections. Less than half are complete, and some only consist of a single volume or even a few scattered pages. Germany stakes the claim to the most Gutenberg Bibles with 14, while the United States has 10, three of which are owned by the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan. The last sale of a complete Gutenberg Bible took place in 1978, when a copy went for a cool $2.2 million. A lone volume later sold for $5.4 million in 1987, and experts now estimate a complete copy could fetch upwards of $35 million at auction.

Subscribe to Gay Wisdom

Would you like to have Today in Gay History (aka Gay Wisdom) sent to you daily?