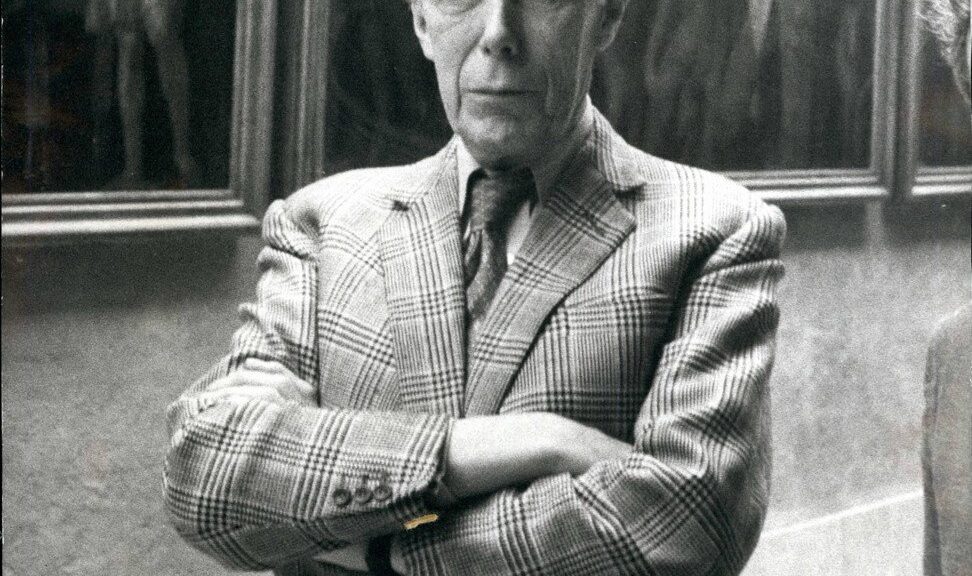

ANTHONY BLUNT, born on this date (d: 1983), styled Sir Anthony Blunt KCVO from 1956 to November 1979, was a leading British art historian who in 1964, after being offered immunity from prosecution, confessed to having been a spy for the Soviet Union.

Blunt was considered to be the “fourth man” of the Cambridge Five, a group of Cambridge-educated spies working for the Soviet Union from some time in the 1930s to at least the early 1950s. He was the fourth discovered, with John Cairncross yet to be revealed. The height of his espionage activity was during World War II, when he passed intelligence on Wehrmacht plans that the British government had decided to withhold from its ally. His confession, a closely guarded secret for years, was revealed publicly by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in November 1979. He was stripped of his knighthood immediately thereafter.

He was a third cousin of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother: his mother was the second cousin of Elizabeth’s father Claude Bowes-Lyon, 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne. He was fourth cousin once removed of Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley (1896–1980) 6th Baronet of Ancoat, leader of the British Union of Fascists, both being descended from John Parker Mosley (1722–1798).

Blunt’s father, a vicar, was assigned to Paris with the British embassy chapel, and moved his family to the French capital for several years during Anthony’s childhood. The young Anthony became fluent in French and experienced intensely the artistic culture available to him there, stimulating an interest which lasted a lifetime and formed the basis for his later career.

He was educated at Marlborough College, a boys’ public school in Marlborough, Wiltshire. At Marlborough, Blunt joined the college’s secret ‘Society of Amici’, in which he was a contemporary of Louis MacNeice (whose unfinished autobiography The Strings Are False contains numerous references to Blunt), John Betjeman and Graham Shepard. He was remembered by historian John Edward Bowle, a year ahead of Blunt at Marlborough, as “an intellectual prig, too preoccupied with the realm of ideas”. Bowle thought Blunt had “too much ink in his veins and belonged to a world of rather prissy, cold-blooded, academic puritanism”.

Blunt was professor of art history at the University of London, director of the Courtauld Institute of Art, and Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. His 1967 monograph on the French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin is still widely regarded as a watershed book in art history. His teaching text and reference work Art and Architecture in France 1500–1700, first published in 1953, reached its fifth edition in a slightly revised version by Richard Beresford in 1999, when it was still considered the best account of the subject.

There are numerous versions of how Blunt was recruited to the NKVD. As a Cambridge don, Blunt visited the Soviet Union in 1933, and was possibly recruited in 1934. In a press conference, Blunt claimed that Guy Burgess recruited him as a spy. The historian Geoff Andrews writes that he was “recruited between 1935 and 1936”, while his biographer Miranda Carter says that it was in January 1937 that Burgess introduced Blunt to his Soviet recruiter, Arnold Deutsch. Shortly after meeting Deutsch, writes Carter, Blunt became a Soviet “talent spotter” and was given the NKVD code name ‘Tony’. Blunt may have identified Burgess, Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, John Cairncross and Michael Straight – all undergraduates at Trinity College (except Maclean at the neighbouring Trinity Hall), a few years younger than he – as potential spies for the Soviets.

Blunt said in his public confession that it was Burgess who converted him to the Soviet cause, after both had left Cambridge. Both were members of the Cambridge Apostles, and Burgess could have recruited Blunt or vice versa either at Cambridge University or later when both worked for British intelligence.

Like Guy Burgess, Blunt was known to be homosexual, which was a criminal offence at the time in Britain. Both were members of the Cambridge Apostles (also known as the Conversazione Society), a clandestine Cambridge discussion group of 12 undergraduates, mostly from Trinity and King’s Colleges who considered themselves to be the brightest minds. Through the Apostles, he met the future poet Julian Bell (son of Vanessa Bell) and took him as a lover. Many others were homosexual and also Marxist at that time. Amongst other members were Victor Rothschild and the American Michael Whitney Straight, the latter also later suspected of being part of the Cambridge spy ring. Rothschild later worked for MI5 and also gave Blunt £100 to purchase the painting Eliezar and Rebecca by Nicolas Poussin.

Some people knew of Blunt’s role as a Soviet spy long before his public exposure. According to MI5 papers released in 2002, Moura Budberg reported in 1950 that Blunt was a member of the Communist Party, but this was ignored. According to Blunt himself, he never joined because Burgess persuaded him that he would be more valuable to the anti-fascist crusade by working with Burgess. He was certainly on friendly terms with Sir Dick White, the head of MI5 and later MI6, in the 1960s, and they used to spend Christmas together with Victor Rothschild in Rothschild’s Cambridge house.

His KGB handlers became suspicious at the sheer amount of material he was passing over and suspected him of being a triple agent. Later, he was described by a KGB officer as an “ideological shit”.

With the defection of Burgess and Maclean to Moscow in May 1951, Blunt came under suspicion. He and Burgess had been friends since Cambridge. Maclean was in imminent danger due to decryptions from Venona as the messages were decrypted. Burgess returned on the Queen Mary to Southampton after being suspended from the British Embassy in Washington for his conduct. He was to warn Maclean, who now worked in the Foreign Office but was under surveillance and isolated from secret material. Blunt collected Burgess at Southampton Docks and took him to stay at his flat in London, although he later denied that he had warned the defecting pair. Blunt was interrogated by MI5 in 1952, but gave away little, if anything. Arthur Martin and Jim Skardon had interviewed Blunt eleven times since 1951, but Blunt had admitted nothing.

Blunt was greatly distressed by Burgess’s flight and, in May 1951, confided in his friend Goronwy Rees, a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, who had briefly supplied the NKVD with political information in 1938–39. Rees suggested that Burgess had gone to the Soviet Union because of his violent anti-Americanism and belief that America would involve Britain in a Third World War, and that he was a Soviet agent. Blunt suggested that this was not sufficient reason to denounce Burgess to MI5. He pointed out that “Burgess was one of our oldest friends and to denounce him would not be the act of a friend.” Blunt quoted E. M. Forster’s belief that country was less important than friendship. He argued that “Burgess had told me he was a spy in 1936 and I had not told anyone.”

In 1963, MI5 learned of Blunt’s espionage from an American, Michael Straight, whom he had recruited. Blunt confessed to MI5 in April 1964, and Queen Elizabeth II was informed shortly thereafter. He also named Jenifer Hart, Phoebe Pool, John Cairncross, Peter Ashby, Brian Symon and Leonard Henry (Leo) Long as spies. Long had also been a member of the Communist Party and an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge. During the war he served in MI14 military intelligence in the War Office, with responsibility for assessing German offensive plans.

In 1979, Blunt said that the reason for his betrayal of Britain could be explained by the E.M. Forster adage “if asked to choose between betraying his friend and betraying his country, he hoped he would have the guts to betray his country”. In 2002 the novelist Julian Barnes asserted that “Blunt exploited, deceived, and lied to far more friends than he was loyal to … if you betray your country, you by definition betray all your friends in that country…”

Queen Elizabeth II stripped Blunt of his knighthood, and in short order he was removed as an Honorary Fellow of Trinity College. Blunt resigned as a Fellow of the British Academy after a failed effort to expel him; three fellows resigned in protest against the failure to remove him. He broke down in tears in his BBC Television confession at the age of 72.

Blunt died of a heart attack at his London home, 9 The Grove, Highgate, in 1983, aged 75. Jon Nordheimer, the author of Blunt’s obituary in The New York Times, wrote: “Details of the nature of the espionage carried out by Mr. Blunt for the Russians have never been revealed, although it is believed that they did not directly cause loss of life or compromise military operations.”