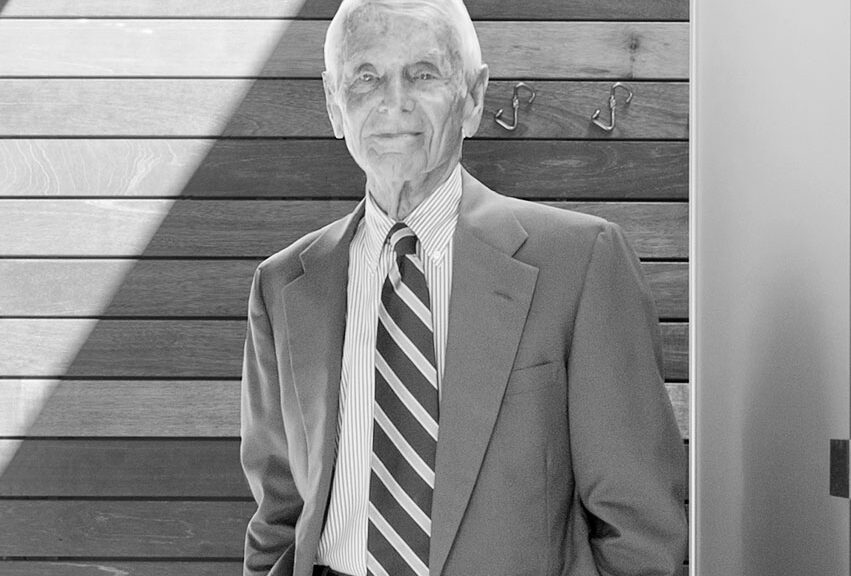

HARRY BATES, born on this date (d: 2022), was an architect who designed scores of modernist houses on Fire Island in the 1960s and ’70s and in the Hamptons in the 1980s and ’90s, and then, with a design partner 45 years his junior, They had a surge of output and influence around the turn of the century,

Harry Bates was raised in Lake City, Fla., the second of two children of Thomas Henry Bates, a country doctor, and Mamie Fairfax Dunstan Bates. Planning to enter his father’s profession, Harry studied bacteriology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill before changing his mind and transferring to the North Carolina State University College of Design, in Raleigh.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1952, he went to work for a Raleigh firm. But as he wrote in the magazine Hamptons Cottages & Gardens in 2016, by 1955 he realized that if he stayed in Raleigh, “I’d probably be doing the same thing 20 years down the line.” So he took a job at the New York office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where he worked on the plans for three now-renowned midcentury structures — One Chase Manhattan Plaza, in the financial district, and the Pepsi-Cola and Union Carbide Buildings on Park Avenue.

When Mr. Bates, working on the East End of Long Island, he met Paul Masi, a young architect and surfing enthusiast who was looking for a job with a small firm. Mr. Bates, then 70, and Mr. Masi, 25, formed a partnership that became Bates/Masi + Architects.

Remembering their meeting, Mr. Masi told Introspective Magazine in 2014: “Here was this sincere, sensitive architect designing timeless houses. I thought, ‘That’s what I’d like to do.’” He added, “I was completely enamored of him personally and professionally.”

By the turn of the century, the partners could barely keep up with demand for their rigorously modern but inviting houses. They were allergic to anything grandiose: When clients wanted large houses, the partners tended to divide them into smaller volumes, effectively disguising them as compounds. They eschewed nonessential details and edited their own work ruthlessly, often limiting themselves to just one or two visible materials.

A house on a hilltop in Montauk is a case in point. Rather than let the building dominate the landscape, Bates/Masi broke its 7,000 square feet into two low pavilions connected by a glass bridge. The exterior is covered in bluestone and cedar and nothing else.

In the introduction to a 2015 monograph about the firm, Paul Goldberger, the former architecture critic of The New York Times and The New Yorker, called the work of Mr. Bates and Mr. Masi “fresh, sharp and original.” Their houses, he wrote, “all had an unmistakable degree of self-assurance, and they were marked by a consistent but very subtle kind of elegance.”

Bates’ life partner of 30 years, Jack Coar, an interior designer, died in 2008.