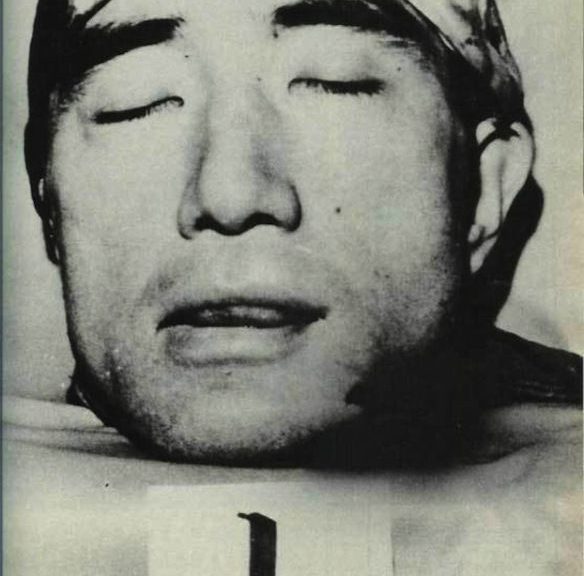

YUKIO MISHIMA, Japanese author, dies (b: 1925) Unlike the West, in Japan sex was not viewed in terms of morality, but rather in terms of pleasure, social position, and social responsibility. While modern attitudes to homosexuality have changed, this is frequently true even today. Like the pre-modern West, only sexual acts were seen as being homosexual or heterosexual, not the people performing such acts. The term gay is never used in discussing ancient and historical sources because of the modern, western, political connotations of the word and because the term suggests a particular identity, one with which homosexuals even in modern Japan may not identify.

From religious circles, same-sex love spread to the warrior class, where it was customary for a young samurai to apprentice to an older and more experienced man. The young samurai would be his lover for many years. The practice was known as shudo, the way of youth, and was held in high esteem by the warrior class.

Like the ancient Greeks, homosexual love was between an older man and an adolescent youth. And like the Greeks, the sexual relationship was expected to end when the youth came of age, at which time he would become the mentor in such a relationship. Just like the Greeks, the Samurai did not practice exclusive homosexuality or exclusive heterosexuality. They were also expected to marry and have children;only this came later in life. Unlike the Greek tradition, it was the younger man’s duty to court the older man. Sometimes the mentor and mentee would remain close friends after the mentee came of age, and other times a homosexual relationship would not end despite the custom.

While male love in Japan existed both before and after the Samurai, Shudo was introduced to the Samurai by Kukai, also known as Kobo Daishi (the great master from Kobo). Kobo was the founder of a Japanese branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, and also the founder of the Shingon school at Mount Koya in 816 A.D. Legend has it that he learned all about nanshoku from China. Ancient China had a thriving homoerotic tradition, including homosexual marriages. Kobo’s school at Mt. Koya became known for Shudo, and its homoerotic literary works. Shudo flourished among the Samurai between the 1200’s and the 1600’s, and declined after that as the Samurai themselves declined in importance.

Before the Samurai, male love existed among Japanese Buddhist monks. It was widely held that their vows of chastity only applied to the opposite sex. After the Samurai, while Japan was in an era of relative peace, male love became more common among the general population and even became commercialized. When it did, male love lost touch with its warrior ideals and sense of honor. Mishima was devoted to the restoration of these ancient Japanese cultural ideals.

On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai, under pretext, visited the commandant of the Ichigaya Camp – the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. With a prepared manifesto and banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d’etat restoring the emperor to his rightful place. He succeeded only in irritating them, however, and was mocked and jeered. He finished his planned speech after a few minutes, returned in to the commandant’s office and committed seppuku. The customary kaishakunin duty at the end of this ritual had been assigned to Tatenokai member Masakatsu Morita, but Morita, also known to have been Mishima’s lover, was unable to properly perform the task: after several attempts, he allowed another Tatenokai member, Hiroyasu Koga, to do the task. Morita then committed seppuku, and then Koga beheaded him.

Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of jisei (death poems), before their entry into the headquarters. Mishima prepared his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members had any indication of what he was planning. His biographer, translator, and former friend John Nathan suggests that the coup attempt was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed. Mishima made sure his affairs were in order, even leaving money for the defense trial of the three surviving Tatenokai members.