TODAY’S GAY WISDOM

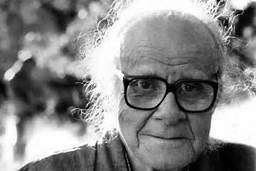

From Harry Hay’s Radically Gay, edited by Will Roscoe:

Harry Hay’s Gay politics represent an alternative to postmodernist, queer theory and dogmatic Constructionism. Indeed, Hay is the only contemporary Gay thinker who could be said to offer a unified theory of Gayness — one that begins by defining its subject in multidimensional terms and then accounts for its individual and historical origins, its diverse forms and their history, the psycho-social development of Gay individuals, and the nature and sources of Gay oppression. Postmodernism offers at best a politics of resignation, one that rejects the possibility of an “outside” to power, of a subject-SUBJECT alternative to subject-OBJECT social relations, and the means of getting there is through a politics that affirms Queer identities and cultures.

Hay is not bothered if his ideas are called Essentialist or if his activism is deemed “identity politics” — he is happy to emphasize his differences with Social Constructionism and Queer theory — provided that the word radical precede these labels. The original meaning of this word, “to the root,” serves well to convey the underlying theme of his philosophy and politics. The key principles of Harry’s radical Essentialism can be summed up as follows:

- It is, first and foremost, Gay-centered — a “situated knowledge” (to borrow Donna Haraway’s terminology) reflecting the social standpoint of contemporary sexual minorities. It is not neutral on the question of Queer well-being; it seeks to create knowledge that contributes to that end.

- It posits Gay presence rather than absence in the usual state of human society.

- It conceives of its subject in multidimensional terms — not merely as sexual preference but as a difference manifest in gender roles, social identity, economic roles and sometimes religious roles, as well.

- It seeks to tell history from the bottom up, using those documents, records and artifacts that reveal the common experience of the largest number of Queer folk and not only the discourse of elite heterosexuals and social institutions.

- It recognizes various levels of meaning — individual, social, trans-cultural, and spiritual. It does not assume that the way an individual describes herself will be identical to the institutional definition of labels that have been applied to her.

- It is multicultural and comparative. Rather than a unitary instance — “the modern homosexual” — it employs the notion of a family tree (like Wittgenstein’s concept of “family resemblance”) to conceptualize the relationship between the Queer identities and roles of different cultures and historical periods.

- It views history as a process of continuity-within-change rather than as a series of sharply defined periods of ruptures. Concept/labels like “Sodomite” and “Urning,” “homosexual,” and “Gay,” have overlapped in their usage. Neither can be defined without reference to the other.

- It focuses on praxis. It seeks to analyze the interaction between individuals and their societies and cultures. It looks for instances of symbols and ideas in action as well as in discourse.

The mass coming-out that transformed the quiescent homophile movement of the 1960s into the dynamic Lesbian/Gay liberation and civil rights movements of the 1970s and 1980s was in large measure a function of joining a community where a negative label could be replaced with an affirmative identity. Hay’s writings show that this was no accident. The cultural minority model was a carefully thought out political analysis and strategy on the part of the Mattachine founders.