December 04

MADAME RÉCAMIER, French socialite born (d. 1849); a Frenchwoman who was a leader of the literary and political circles of the early days of the French Consulate to almost the end of the July Monarchy, and considered to be the most beautiful woman of her time.

Born in Lyon and known as Juliette, she was married at fifteen to Jacques Récamier (d. 1830), a rich banker more than 30 years her senior. At the time, it was said that he was in fact her natural father who married her to make her his heir.

Beautiful, accomplished, with a real love for literature, she possessed at the same time a temperament which protected her from scandal, and from the early days of the French Consulate to almost the end of the July Monarchy her salon in Paris was one of the chief resorts of literary and political society that pretended to fashion. The habitués of her house included many former royalists, with others, such as Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte and Jean Victor Marie Moreau, more or less disaffected to the government. This circumstance, together with her refusal to act as lady-in-waiting to Empress consort Josephine de Beauharnais and her “friendship” for Anne Louise Germaine de Stael, brought her under suspicion.

When a history says someone’s sex life is “unconventional” it can sometimes mean little more than the subject enjoyed something other than the standard missionary position with his clothes on and the lights off. When a woman’s sex life is even mentioned, no less described as “unconventional” then you better sit up and take notice. Madame de Stael was such a woman.

In 1798, separated from her own husband and living with yet another male lover, she met up with Madame Anne Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein, commonly known as Madame de Staël. De Staël was 31, Juliette was ten years younger. “She fixed her great eyes upon me,” wrote Juliette, “and paid me compliments about my figure which might have seemed exaggerated and too direct had they not seemed to have escaped from her. From that time on, I thought only of Mme. de Staël.” They lived together for the next nineteen years until de Stael died. Her final words to Recamier, to whom she had once written, “I love you with a love that surpasses that of friendship,” were “I embrace you with all that is left of me.”

RAINER MARIA RILKE, Austrian poet was born on this date (d. 1926); Austria’s greatest modern poet is included here because Harold Nicolson, who knew him, and whose perception generally demands consideration and respect, believed Rilke to be Gay. W.H. Auden once dismissed Rilke as “the greatest Lesbian poet since Sappho.” Since Auden wasn’t on particularly good terms with Harold Nicolson, it’s more than likely that he came to his own conclusion about there being something “different” about the poet. For many years, Rilke lived in Paris, where he was secretary to the sculptor Augúste Rodin, himself supposedly Gay. Since Rodin was an intimate of Diaghelev and Nijinsky, it seems unlikely that Rilke did not move in the same fay circle. Cocteau, for example, knew the poet and even invented a story that Rilke had been in love with him. Once again, a good modern biography is needed. There seems to be too much “in the air” to ignore.

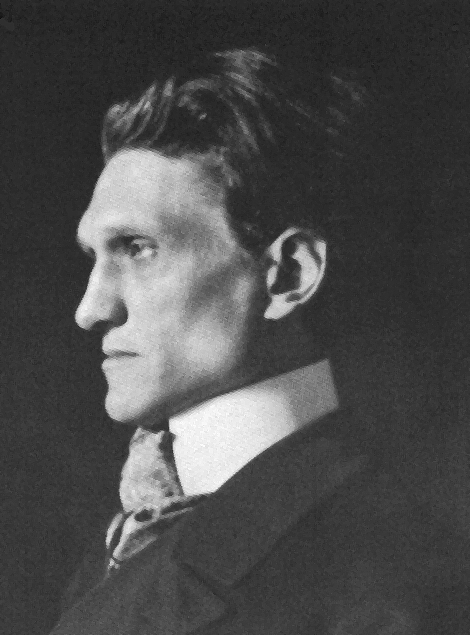

STEFAN GEORGE, German poet, translator and editor, died (b. 1869); George was an important bridge between the 19th century and German modernism, even though he was a harsh critic of the then modern era. He experimented with various poetic meters, punctuation, obscure allusions and typography. Inspired by Mallarmé's coterie of writers and artists in Paris, George formed his own circle that was known as the Georgekreis (George-Circle). Indicative of George's elitism, he founded a literary journal, Blätter für die Kunst (Pages for Art), which was available only to the members of his circle.

A strong authoritarian personality, he founded his circle on the master-disciple relationship. His devotion to the artistic paradigm of "art for art's sake" manifested itself in his desire to shape his reality according to his aesthetic ideals rather than to society.

George's sexuality is an open secret in the scholarship about him; that is, it is a commonplace that almost no one will admit. George, however, is as responsible for this closetedness as anyone since he strove in his work to create a private space that would be accessible only to those "like-minded" individuals who possessed the code.

Therefore, his poems allow themselves to be easily construed as "metaphorical" or "platonic," even if they most immediately appear to be about burning Gay passion. George accomplishes this effect by addressing a genderless "you" in his poems and by personifying such terms as "love," "soul," and "heart."

Two works, Algabal (1892) and Maximin (1906), especially embody a Gay sensibility.

Algabal is a young king who builds himself a subterranean kingdom, the artificiality of which surpasses the natural beauty of the world above. The significance of the embrace of the Unnatural, the Barren, and the nonetheless Beautiful in this work cannot be missed by the reader aware of the stereotypes of Gay love, but is simply readable as decadence to one who is not. The poem's dedication to the memory of the Bavarian king, Ludwig II, a homosexual icon at the turn of the century, is also a signal to its gay meaning.

Maximin was inspired by the Munich high school student, Maximilian Kronberger, whose early death served as an excuse to mythologize his memory. Although the youth's poetry was the overt excuse for his relationship to George, the poetry's mediocrity suggests that George encouraged Kronberger mainly because of his physical beauty.

George was thought of by his contemporaries as a prophet and a priest, while he thought of himself as a messiah of a new kingdom that would be led by intellectual or artistic elites, bonded by their faithfulness to a strong leader. His poetry emphasized self-sacrifice, heroism and power, and he thus gained popularity among National Socialist circles. A group of writers that congregated around him were known as the Georgekreis. Although many National Socialists claimed George as an important influence, George himself was aloof from such associations and did not get involved in politics.

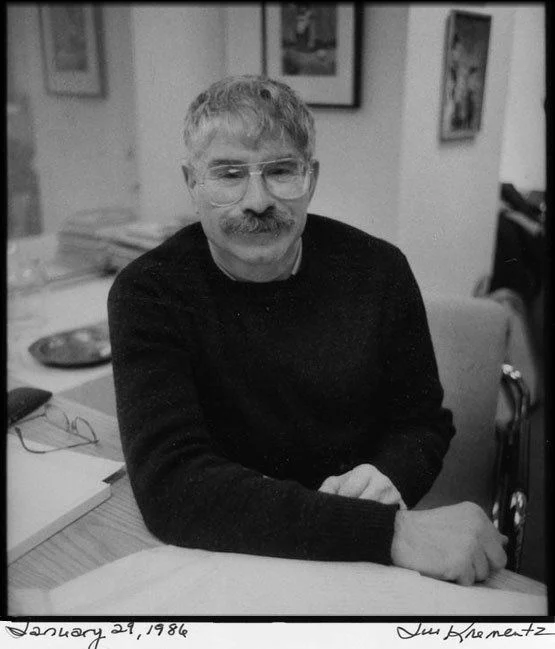

ARNOLD LOBEL was an American author of children's books who died on this date (b: 1933); He is best known for his Frog and Toad series and Mouse Soup. He wrote and illustrated these picture books as well as Fables, a 1981 Caldecott Medal winner for best-illustrated U.S. picture book. Lobel also illustrated books by other writers, including Sam the Minuteman by Nathaniel Benchley published in 1969.

Lobel was born in Los Angeles, California, but was raised in Schenectady, New York, the hometown of his parents. Lobel's childhood was not a happy one, as he was frequently bullied, but he did love reading picture books at his local library. He attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. In 1955, after he graduated, he married Anita Kempler, also a children's writer and illustrator whom he'd met while in art school. The two worked in the same studio and collaborated on several books together. They had two children: daughter Adrianne and son Adam Lobel, and three grandchildren.

Following college, Lobel was unable to support himself as a children's book author or illustrator and so he worked in advertising and trade magazines, which he did not like.

But he loved his writing and illustration work, saying "I cannot think of any work that could be more agreeable and fun than making books for children" and described his job as a daydreamer. He began drawing during a period of extended illness as a second grader. On the October 25, 1950 episode of "Kukla, Fran and Ollie", Oliver J. Dragon presented "poems by Thomas Smith and drawings by Arnold Lobel from Schenectady."

His professional career began during the 1960s, writing and illustrating "conventional" easy readers and fables. His style could be described as minimalist and frequently had animals as the subject matter. Lobel used animals as characters because he felt it helped with the suspension of disbelief.

His second book, A Holiday for Mister Muster, and perhaps others were inspired by the Prospect Park Zoo in Brooklyn, which the Lobels lived across the street from. Cartoons his children watched were also an inspiration, as were popular television shows like Bewitched and The Carol Burnett Show.

Lobel's writing and illustrations went through several phases in his career. His early works had a broad humor often in verse, a style that he would return to at other points in his career. In 1977 interview for The Lion and the Unicorn, Lobel explained that he wrote these books by imagining what children would want to read. However, as he continued to write, he realized the books he was writing didn't have the "weight" to them he wished and that he was going to have to use tap into himself in order to create better writing.

Following that epiphany, he began taking inspiration from his own experiences and emotions, and acknowledged that he was writing "... adult stories, slightly disguised as children's stories." In the 1970s Lobel's illustrations shifted from primary colors to a broader spectrum of pastel colors. The solitary individual, whether played seriously or for comic relief, was common in Lobel's work, as were two people who were complementary.

Lobel's illustrations served to visualize the rhythm and emotions of the text in a way that could be "cinematic." His chosen vocabulary, subject matter, and writing style helped to re-conceive what an easy reader book could be. Lobel identified the exploration of his own feelings as a reason that he improved as a writer.

In his 1977 The Lion and the Unicorn interview, Lobel discussed the ways he would work through his emotions while still maintaining his children's audience. This was part of Lobel's belief that adult and children emotions were more similar than different. His work was described as "sunny, warm, even cosy." Despite this, the process of writing was "painful" for Lobel, who was far more inclined to want to illustrate than write and only started writing because of the increased royalties. As late as 1983, Lobel felt he was beginning to trust his instincts as a writer. In fact, he never felt comfortable enough with his technical writing skill to consider writing a novel for adults, or a longer book for children.

Lobel illustrated close to 100 books during his career which were translated into dozens of languages. Despite the awards he won, Lobel wasn't always recognized during his lifetime.

In 1974, he told his family that he was gay. In the early 1980s, he and Anita separated, and he moved to Greenwich Village. He died of cardiac arrest at Doctors Hospital in New York, after suffering from AIDS for some time.

The musical A Year with Frog and Toad (workshopped 2000, premiered 2002), by Adrianne Lobel and others, played on Broadway in 2003 and has toured nationally since.

Subscribe to Gay Wisdom

Would you like to have Today in Gay History (aka Gay Wisdom) sent to you daily?