Circle Voting

Circle Voting

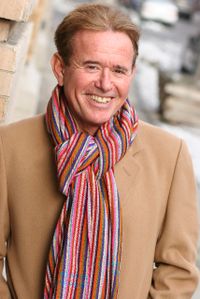

A White Crane Conversation with Murray Edelman

By Bo Young and Pete Montgomery

Murray Edelman was the editorial director of Voter News Service, a consortium of ABC, CBS, CNN, FOX, NBC, and the Associated Press that famously was involved in the 2000 Bush/Gore contest and the fate of the Florida vote. He helped develop the first exit polls and has conducted them for over 20 years. One of his legacies is the only continuous body of Gay/Lesbian voting data from the exit poll since 1990. Edelman received his BS in Mathematics from the University of Illinois and his PhD in Human Development from the University of Chicago in 1973. He has been the only openly Gay President of the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR), the largest and most influential body of survey research professionals.

While a graduate student in 1969 at the University of Chicago, he co-founded a Gay liberation group that became the powerful Liberation Movement in Chicago and the around the Midwest. In 1973 he moved to San Francisco where he co-founded the first modern day Faerie Circle with Arthur Evans. He led ground breaking intimacy and sexually weekends for Gay men and “a Different Kind of Night at the Baths” that Joseph Kramer has cited as one of his inspirations for Body Electric. Harry Hay invited Murray to present his work at the first Radical Faerie conference in 1979. He studied and taught an intensive meditation in the 80s and is currently president of the Naraya Cultural Preservation Council (www.ncpc.info) and is an elder in that Naraya community, which he has been part of since 1991.

Bo Young and White Crane Board member, Pete Montgomery, sat down for a discussion with Edelman about a current project he is working on, Circle Voting.

Bo: Tell us about Circle Voting Murray.

Murray: Circle Voting is voting as a community concerned about the future: the environment, education, our health, our rights, Some people follow politics a lot, like some people follow sports, while others could care less about politics. But when only half of the community votes in the community’s interest we all lose. I use “circle” because each of us is part of many communities but the principle is the same. In Circle Voting, those that are politically motivated encourage others of like mind to vote and share their information and vote choices so that the community has the biggest impact.

Bo: Why the emphasis on sharing information?

Murray: From many years of political discussions with my spiritual friends, I’ve learned that many people, including two important teachers to me, are confirmed nonvoters and many others are occasional voters. Basically they don’t want to put any energy into the fear, anger and melodrama that is so much a part of politics. I think that is a good reason to not spend much time on politics. But I don’t think it is a good enough reason to not vote. So Circle Voting can serve as a shortcut for users to vote in their own interest in minutes.

Peter: How does this sharing of information work?

Murray: It is common for organizations to endorse candidates. Sometimes the endorsements take the form of a voter guide and sometimes it is a palm card to be taken into the voting booth.

In Circle Voting, we will collect endorsements from organizations as well as encourage politically motivated users to enter their own recommendations and the reasons for them. The user recommendations would be only available to friends of the user, while the organizational ones are already publicly available.

Users will then be able to create a Council of Advisor from like-minded organizations and friends and by entering their locality, create their own personal voter’s guide from these endorsements summarized for every race on their own ballot. And then they can click down for the reasons.

Bo: Where can a reader find Circle Voting?

Murray: At www.circlevoting.com. You can see plans for the personal voters guide. I hope to have an abbreviated version online for this election. The other tools, such as registering to vote and applying for an absentee ballot will be online by the time this is published. I am hoping to be an application on Facebook, but that might have to wait until next year. Perhaps one of your readers could conjure up a Facebook developer for me?

Peter: Is this like Move On or other organizations of like minded people?

Murray: Circle Voting is inspired by the past successes of the Religious Right and labor unions. And the success of the Religious Right is way out of proportion to their numbers because they have mobilized the less motivated voters to turn out consistently and in state and local elections. They put a lot of pressure on their members to vote and provide Voting Guides to identify the good “Christian” candidates.

Murray: Circle Voting is inspired by the past successes of the Religious Right and labor unions. And the success of the Religious Right is way out of proportion to their numbers because they have mobilized the less motivated voters to turn out consistently and in state and local elections. They put a lot of pressure on their members to vote and provide Voting Guides to identify the good “Christian” candidates.

MoveOn, like the Religious Right and labor unions, make endorsements. They also raise money and often help in the campaigns. Circle Voting does not make endorsements. It only collects them. There is no fundraising and involvement in the campaigns. There is really no organization here; just enough to keep the website going.

Peter: Is it a voter education process or a get out the vote drive?

Murray: It is more of a “bring out your own” voter drive. Bring them to Circle Voting where they can get help in registering or applying for an absentee ballot and then later get your recommendations and have a dialogue about their reluctance to vote and suggest new ways to look at voting.

Currently, voting is seen as a private act and I think that is conducive to many people not voting in their own interests. Voter education puts the burden on the voter and I think it is too much of a burden especially since the candidate do everything they can to confuse the voter.

We don't know how most software works, but we know people that can help us. We don't see every movie, but we know people of similar taste that see movies. Similarly we can make votes in our best interest by relying on like minded friends and save a lot of time and energy.

Bo: I'm interested by the idea that people are voting against their personal interests…I was speaking to a single mother the other day, from Texas, and she was ready to vote for John McCain even though, as we spoke, it became clear that this was against her own personal interests….so how would Circle voting work in this one-on-one setting?

Murray: If she was basing her choice from following the news etc, it CV wouldn’t mean much. But many voters don't have much information when they vote. That’s why negative ads are so effective. This person might see summarized the voting preference and reasons from people in her circle of like mind. She could see the endorsements from groups that represented her interests. This could all be presented in a nice easy

Peter: A quick look at Circle Voting makes me think it could be especially useful for down-ballot races – so many people, including me, show up and know next-to-nothing about a school board race, or judge – but if I saw how what some neighborhood activists thought, that would help shape my thinking."

Murray: Right, Peter. I got this idea because in local election in New York, I always call a friend that was very active in local politics and ask him who to vote for. Circle Voting could become very important in a state or local elections where a few additional votes can make a difference in zoning or a position on the school board. I am looking forward to the New York City primary in September.

Peter: Could you articulate the spiritual principles underlying Circle Voting ?

Murray: I’ve seen so many times that when we come from a place of an open heart and connection with spirit, we see abundance and possibilities everywhere. When we come from fear and anger, we see limitations and create more divisions. Politics today thrives on the latter, possibly more so now than ever.

Many avoid voting for this reason. But haven’t you found that which you avoid, usually comes back to haunt you? You know, what Jung call “shadow.” There is a parallel here. It really doesn’t matter if 30% or 40% vote. What matters who wins, and mathematically a non-vote is the same as a vote for the winner. So, for example, that non-vote, in a local race, could have helped elect that official that just caved in on an important zoning issue involving some land that you love.

I believe when we focus on our hopes and dreams, we draw upon limitless energy. My love of Mother Earth strengthens me. When we can tie voting to what matters to us, we will want to talk to people about it, we will want to vote and we will want to encourage others to vote. A current choice of candidates is just a short term choice, and not much more than that. But, it is still an important action.

So Circle Voting is a way to come into balance with politics. In a sense, take responsibility for our actions and inactions. The important thing is informed voting, not some old idea of “getting involved” in politics. It only needs to be a few minutes of time, but it is a lot better use of time than even a few minutes of recycling. And it is another way to act in community, by supporting the judgment and research of people of like mind.

Bo: OK…I’ll ask the question we all hear: But does one vote really matter that much?

Murray: In our spiritual work, we’ve seen the ripple effect, how one person’s changes affects others. Each reader that comes into new consciousness around voting will affect many others .and if they pass on the link to CircleVoting.com so much the better. So you could live in New York and effect votes in a key state like Virginia just from the ripple.

And we know the power of attraction: the energy and intention that we put out brings us what we need. In politics, it is the same. It is not an accident that for the most part conservative candidates are elected where there are conservative voters. Green party candidates appear where there is support for them. But bringing out our vote especially in local elections where only 5% to 10% vote, we could encourage a lot of new and creative candidates to run.

Bo: It sounds almost like you are suggesting a new kind political consciousness.

Murray: In a sense it is. It is putting elections in their proper place. We must participate at every voting opportunity, but we don’t have to do much more than that. And we don’t have to necessarily agree with each other. If this consciousness were to grow in a big way, it could really affect the political system. You’ve probably heard “Money is the mother’s milk of politics.” It is even more true today with our first billion dollar presidential campaign. Money is important because it allows the candidate to control their message especially close to the election and to bring out their vote and depress the other candidate’s with negative campaigning.

As more and more people avoid all this misinformation, and yet still vote regularly, the money will have less impact. New candidates, not beholden to their large contributors will have a chance.

Bo: You mentioned something to me in an earlier conversation…a factoid about how many people say they intend to vote…and then how many people actually vote…"

Murray: Most people I talk to say, "All my friends vote.” So they don't need this…

Bo: I would certainly say that.

Murray: But here is some hard data: In late October 2004, 81% in a CBS News/NY Times poll said that they would "definitely vote" or they had already voted." Yet the comparable number of actual voters in 2004 is 55%. That means 26% were sure they would vote but didn’t. And I didn’t include the ones that said they would "probably vote".

And let’s not bury the lead here. Once we remove those ineligible to vote, we end up with 40% did not vote in the highest turnout election in decades. And the number is even higher among those making under 100K and also those 18-25. Know any people like that in your own circle?

Another survey factoid: The previous number was about intention to vote. How about what they remember about voting? In July 2008, 86% in a NBC/Wall St journal Poll said they voted in November 2004." Now, 31% of the people said that they actually voted, when they didn’t really vote.

Bo: So is this one of those 'telling the pollster what they want to hear’? Or what the respondent thinks is the "right" answer?" “Good” citizens vote so I'm going to say I voted, even if I didn't.

Murray: Perhaps. They are telling this to a stranger; that they did the socially approved behavior. But what do they tell friends? How many people do you know who advertise that they didn't vote? I submit only the confirmed nonvoter.

And given my own informal survey in different spiritual groups, I suggest that each of your readers is surrounded by nonvoters in their own circles, perhaps as many as half of them. What a great place to start if you care about the environment, etc. And in a state and a local election where the turnout is much lowers, there are lots more nonvoters in our own circles.

Bo: So Circle Voting is a kind of "focused peer pressure"?"

Murray: It is using the power of social networks. There is research showing that people are more likely to quit smoking if those in their social networks have quit and that they are more likely to gain weight if those in their social networks gained weight. The point is we are linked in many ways — obviously not an original thought — but our interdependence is growing and voting can and should reflect this more. This could be used to access other viewpoints. It is up to the person to pick those that they want to hear from."

Peter: So part of the power is the connection — an individual, in a circle, is also the center of his or her own circle, etc. How the 125 people I'm attached to on LinkedIn gives me access to something like 100,000 friends of friends, etc, etc.

Murray: The Religious Right clearly knows the importance of mobilizing their members, especially those that are not involved politically. And yes, Peter, that is how it could grow. The catch is getting it moving.

Bo: In a way, isn't this how the Obama campaign has been functioning? They've sort of plugged into the internet and used it in brand new ways to network…

Murray: Yes. Obama is using the net really well.

Bo: Would you call what he's doing "circle campaigning"?

Murray: You could probably say Obama is doing that. The difference is that his people are pushing his brand and that is important in getting out his vote.

Bo: Wouldn't I or Pete be pushing our set of ideas in my circle vote in the same way?

Murray: My vision is that the networks in Circle Vote could persist from election to election and promote progressive ideas. I think the approach is different. In “Obama-land, someone would be saying “Vote for Obama — I'll help you.” In Circle Voting that individual would be saying, “We are of like mind. It is in our interest that we vote regularly. Here are my thoughts. I hope other friends will offer you theirs.

Bo: I think the interesting thing is to get people out of the immediate circle of "people who agree with me" and bring them into contact with new ideas. It seems to me one of the biggest social problems we are facing, something that seems benign, is that we all tend to read the papers and watch the programs and listen only to the ideas with which we already agree. Everyone on the spectrum is constantly seeking affirmation of their own point of view…how does Circle Voting move people past that…or does it?"

Murray: I agree there is a lot of segmenting of thought.

Peter: Even among my circle of lefty friends we have our annual and quadrennial debates about voting for the Democrat versus voting Green or sitting it out because the two major parties are both corporate, etc… This could create online space for some of those debates…of course so do a lot of blogs.

Bo: This whole idea is an interesting hybrid of your professional work and your personal work …can you talk a little about that?"

Murray: Let me answer by telling you more about how this vision came to me. I was at a Faerie fire after the Naraya at Wolf Creek sanctuary. Earlier that day, I had given a talk about my early Gay liberation days and how we took chances and followed our hearts. We had visions, but none of them were very accurate. But something wonderful came from our courage and insight. And we didn't know what at the time.

So at this fire, they were doing a very typical Faerie thing of trashing the government. For different things and there is no shortage of things to find fault with, of course. And at one point I started a chant "Think bigger, think bigger…" They really got into it, as Faeries do, and then they asked "What should we do?" And I said "vote” …and it caused a great deal of chaos. And in that chaos, I saw how much I had to say about how things really work and that is what I've been working on since."

It was like my whole life was integrating before me — all my Gay liberation, Marxist days, along with all my years of in politics and media and surveys. The struggle has been to articulate this and create a place where people can see it working. So Circle Voting could energize our community to use their interlocking networks, where there are some that really know politics to inform and encourage the very many that just don't care." And as I worked with it, I saw that could apply to many communities.

In my earlier days, I thought that a vision was more of an endpoint, a solution. But this energy just keeps propelling me into some of my more difficult spaces, like being articulate. This interview process has helped my clarify things a lot. But it has also been very difficult for me. So my advice to people looking for a vision: Be careful what you ask for.

Bo: If I have one problem with people in general it is that I think a lot of them would often rather sit around and complain than act. Because acting runs the risk of failure. So nothing happens, but a lot of complaining and kvetching and everyone gets to feel catharsis and they go home. You're calling on people to act and to interact"

Peter: I'm now seeing the spirit and ethic of the heart circle in your proposal. Creating an online circle and speaking from the heart — and in ways that help people decide how to take meaningful action.

Murray: Yes and I just need a few people to buy into it. Because it really is easy. We need people to cast votes in their interest. We don't need them to read and understand “politics" per se. That is a losing cause.

Bo: I know personally it is one of the reasons I withdrew from my active political involvement. Politics is, by its nature, a win-lose proposition. Someone always wins. Someone always loses. You’re asking that people find win-win communities…where shared interests and shared objectives benefit everyone in the community. In a way…no, in fact, it's co-opting what the mega-churches and the radical religious right has been perfecting for a decade or more…and they’ve shown that it works.

Murray: Yes. In a sense it is empowering people by using existing relationships of community. There is a similarity to the religious right, but that is still top down. I can’t see the progressives I know acting top down. There is a kind of anarchism in this in that circles can form in different ways in different times. There is no one calling the shots here. Water is finding its own level. Circle Voting would empower people in voting by using their existing relationships of community and create a synergy with those knowledgeable about politics with those of like mind but not that concerned or immediately involved. Independents probably experience this in general elections.

Bo: What would you like to see readers of this conversation do then? Presumably people reading are likely to be "like-minded.” And what attracted me to your idea is that White Crane has always set as its mission "a deeper relationship with yourself and your community" and you are inviting people to do just that in a very pragmatic way"

Murray: I would ask readers to check out www.CircleVoting.com. Give me feedback and join the circle. The next step would be send emails to like-minded people in their own circles, encouraging them to check it out. It could be one email or a series of up to three.

The first email could also encourage registration, saying that 10% of the people think they are registered. But they aren’t. And many don’t register because of the mistaken belief that immediate become eligible for jury duty. A second email could offer this Circle Voting as a place to get an absentee ballot. A third email, close to the election, could offer the personal voting guide (if available) and encouragement to vote.

Bo: Aren’t you concerned about creating a lot of spam from this?

Murray: I brought that up with my computer person and he said that was a good problem to have and there will be ways to avoid that.

Bo: Anything else?

Murray: Yes, take stock of your own voting behavior. Do you vote in all local elections? Do you take the time to make an informed vote? And could you imagine what would happen if enough people really did make informed votes on the issues of the future that really mattered to them?

For more about Circle Voting visit www.circlevoting.org