Opening Words from the Editors

Our Special Role

Dan Vera & Bo Young

Bo: So this was an issue long in the “a-borning” process.

Dan: Gestating?

Bo: We’ve had the germ of this issue for almost two years

Dan: Wow. Has it been that long?

Bo: Victor Marsh’s interview with Don Bachardy sat for a long time until we could figure out how to present it. I’m not really sure “Beats & Bohemians” is the right rubric for it.

Dan: Well we have talked about the term “Beats” being a misnomer. “Beats” was coined from “beatific” and applied by people outside the movement. It was an invention of the press, if memory serves.

Bo: And that “Bohemian” is a term that stretches from the turn of the century.

Dan: Yes. Andrew Ramer writes about the confusion-inducing nature of that term in his column this issue.

Bo: I think the idea is about “outsider” being “different” and the perspective that offers. And “Bohemia” has always seemed like a place where the sexual “transgressive” fit in. Andrew Ramer talks about it in his column, how there was this perception of sexual freedom right from the earliest notion of the term. I remember in my own “coming out” days wanting to get away. The Hippies were the bohemians of my youth and I wanted to be one.

Dan: What was it about them that attracted you?

Bo: The pretty men with long hair. The whole communal thing and the experimental nature of it all. They were trying out new ways of being in a time when I didn’t think much of the way I’d seen things being done. I wanted nothing so much as to put as much distance between me and Suburbia as I could. And Suburbia is still the only place I’m afraid of – that Stepford effect.

Dan: There is a geographic element to this discussion. I’m reminded of Edward Field’s recent memoir on the Bohemians of New York’s Greenwich Village after World War II. He writes about how they found this enclave where they were free to explore their lives and their art.

Bo: The dictionary’s first definition of “bohemian” is geographic. The second is about people who “live and act free of regard for conventional rules.” It’s about being unconventional.

Dan: Sure, but the question is what happens when the conventional rules change. Being gay in Chelsea or Washington DC’s Dupont Circle is not an act of brazen liberty is it?

Bo: No, but it was when those neighborhoods weren’t so trendy we made them trendy. In fact I’d go so far as to say we fix cities we settle areas that others desert.

Dan: So trendyness is today’s bohemianism?

Bo: No. That’s the wake, the afterward. It is about pioneering.

Dan: So Bohemianism gives birth to banality.

Bo: Only when it gets commodified after the true bohemians have moved on. It’s just one of the social roles that same sex people have always played. I don’t think it’s simply a subset of the group that sexual freedom is part of it. I think in some ways it defines it.

Dan: Where have they moved to? I guess that’s what I’m curious about. Cause I go back to the theory that Bohemianism has a direct relation to cheap rent. Allen Ginsberg could live on unemployment and do his art.

Bo: Oh yes. Cheap rent is very much a part of it. Except after the bohemians move in, the rents end up going up. We make it safe and profitable

Dan: So, I’m just asking the question that cities may not be where Bohemianism is living today because people can’t make art free of constraints if they’re working for Smith Barney to pay the rent. I was reminded from our recent time there that the same is true of the Castro. I’m sort of haunted by the conversations we had there with artists who struggle to make sense of what’s around them.

Bo: Well, there are surely “bohemian” people in rural places, too. I don’t think “bohemia” as a concept has a geography, per se. There are rural bohemians, and there are urban bohemians. The connection is living outside the boundaries, and moving the boundaries. It gets back to the traditional social role of same sex people, to my eye. It’s another “contrary” role – the “re-interpreter.”

Dan: I don’t think people struggled to create communities or neighborhoods so they could be co-opted. I think they wanted more – still want more. I don’t think the end result was to be tastemakers. That’s way too safe and we didn’t need liberation to perform that function—those of us who perform that function (not all of us do of course).

Bo: Oh I agree. I think the motivation is about finding a better, more satisfying way to live—unconstrained by social rules that have become constraints.

Dan: Well by most definitions the movement’s sort of hit a wall. I think the social rules can only apply if you’re living in Anniston or Pagosa Springs.

Bo: I don’t know those references.

Dan: Anniston, Alabama or Pagosa Springs, Colorado. I was just referencing more rural locales.

Bo: I think that’s the whole point. There isn’t any one “movement.” Bohemia is about the individual. The minute it becomes a “movement” it’s something else.

Dan: No. I disagree. The Beats, as we call them, were not individuals. That’s a total myth. They functioned and “succeeded” through their collective efforts. The reason we know of Burroughs and Kerouac is because of Ginsberg and the reason we have Ginsberg – as David Carter’s piece demonstrates beautifully – is because of his interaction with Burroughs and Kerouac. Ginsberg championed his friends’ work when no one would pay any attention. If the world loves On The Road, they owe a debt of gratitude to Ginsberg who used the his Howlfame to push for its publication

Bo: I think that’s the other side of this, too. All these radical “individualists” like the Goths now, or even the Hippies all dress alike, all look alike. It becomes about being identifiable. There is always this regression to a mean. But I think that is precisely what the “true bohemian” is responding to.

Dan: Sure. “The 50s begat the Beats which begat the Hippies, which begat the Punks” etcetera, but it sort of falls apart somewhere there at the end.

Bo: But there’s always one, or a few, who wander off and try to reestablish some individuality. It’s a very scary place to live, though, and it is certainly one of my interests with respect to modern gay folk. Getting back to Harry Hay’s whole idea that “the bedroom is the only place we’re like straight people.” It’s amazing how threatening that is to a large group of gay people and how easy it is to slip back into that Stockholm Syndrome of trying to convince hetero-society that we’re “just like them.” And how really difficult it is to stand outside and declare your differences. But this issue seems to confirm how important that is.

Dan: I just had a conversation with an artist we both know. He’s devoted his entire life to living simply so he can do his art. I asked him if he knew where the gay bohemians were today. His reply was a question. “Is there such a thing? I thought gay was part of the norm now so that we don’t need to live in special areas.”

Bo: Well, that is interesting. But for me it reinforces that the whole “gay lib” thing isn’t about sex. It’s about social roles. Sex is just sex, like Harry says. It’s the only place we’re the same as “them.” It’s every other way that makes us another “them.” As desperately as people will try to hold on to being “just like everyone else.” The feeling that it’s important to “fit in” is deeply tribal. It’s scary to be on the outs or feel like you’re on the outs. I think the point is that we actually have a special role and the sooner we go about defining it the better off we’ll all be.

Dan: What are some of those roles?

Bo: One of those roles is to be the outside commentor – the perspective that being outside, even briefly, offers. That’s very important for culture and society. Sometimes that outsider role is the joker, the jester making fun of things. That’s revolutionary by definition. And sometimes it is as the contrary: deliberately going against the flow. These are all definitions of “bohemians.”

Dan: I just think it’s near impossible to do that from a point of comfort. And we’re way too comfortable as an enclave. Chelsea is way too comfortable and cozy. Part of the dynamic is the carving out of space that is other, that is protected – a liberated zone if you will. Is there any chance to break from the rootlessness of that role? I mean to actually put down roots in a community? To not be the cultural interior decorator for the society or for realtors?

Bo: Well, for me that’s the point. “Bohemia” isn’t geographic. It’s a state of mind with very strong ego boundaries. Rootlessness is another synonym. They just don’t want to be confined by convention.

Dan: Maybe we’re challenged by trying to talk about them in general terms. Maybe it’s about intentionality. How you do things authentically.

Bo: There is a social co-dependency that is considered “the norm.” It’s easy if you fit in but not so easy if you don’t. Some people get bent out of shape with it all. Still others turn it into an art form. “Life as Art.” Which is certainly what Mr. Bachardy is doing.

Bo: There is a social co-dependency that is considered “the norm.” It’s easy if you fit in but not so easy if you don’t. Some people get bent out of shape with it all. Still others turn it into an art form. “Life as Art.” Which is certainly what Mr. Bachardy is doing.

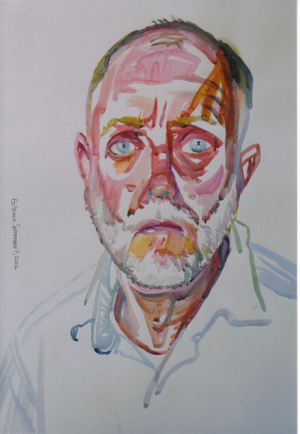

Dan: It’s a big thing for our humble and solid little publication to be printing four of Don Bachardy’s nudes in this issue. They are truly works of art and they signify a threshold for us in keeping to our mission. You had the chance to sit for him. What was that experience like?

Bo: It was an honor to sit for him and fascinating. He works so fast and the concentration and meditation he speaks of in this interview, is palpable. There is a clear connection made with him as you sit there and his laser eye takes you in and translates you into color on the page. I think it’s Fauvist (another bohemian split from the art establishment in its time!) He really colors outside the lines. But I really got a sense that he lives to paint.

Dan: That may be the purest way to understand this issue. To talk about life as art. Or the pursuit of art. But I don’t think it has much to do with these creators thinking of themselves as Bohemians. It had more to do with their being honest about their lives and their expression of that liberated life through their art. I think these larger sociological conversations are just dead ends. They get too convoluted. Just sound like catch-phrases. Maybe because so much of the language has been co-opted on to Gap Ads.

Bo: Well I think that’s certainly true. Everything and everyone is capable of being coopted. But there will always be bohemians. Whatever they call themselves.

This is just an excerpt from this issue of White Crane. We are a reader-supported journal and need you to subscribe to keep this conversation going. So to read more from this wonderful issue SUBSCRIBE to White Crane. Thanks!

Bo Young and Dan Vera are editorials mid-wives and co-conspirators in creating each issue of White Crane. Bo lives in Brooklyn, NY a few blocks from a museum and Dan lives in Washington, DC a few blocks from a Shrine. Bo is the author of First Touch: A Passion for Men and Day Trilogy and Other Poems. Dan is the author of two chapbooks of poetry, Crespuscalario and Seven Steps Up. If they sometimes seem interchangeable in the minds of White Crane readers it’s because they talk on the phone each day and bask under the shade of the same growing tree, the watering of which they consider their contribution to the continued flowering of gaiety.

Eight Publishing Triangle Awards were presented to various men and women, including The Randy Shilts Award for Gay Nonfiction, which was awarded to Kenji Yoshino (at the left), for his groundbreaking and important book, Covering. Other nominees in the category were Bernard Cooper for The Bill from My Father and Rigaberto Gonzalez for the beautiful and poetic, Butterfly Boy.

Eight Publishing Triangle Awards were presented to various men and women, including The Randy Shilts Award for Gay Nonfiction, which was awarded to Kenji Yoshino (at the left), for his groundbreaking and important book, Covering. Other nominees in the category were Bernard Cooper for The Bill from My Father and Rigaberto Gonzalez for the beautiful and poetic, Butterfly Boy.

Poets Jennifer Rose and Justin Chin won, respectively, for Lesbian and Gay Male poetry. Justin’s Gutted was nominated along with Jim Elledge’s A History of My Tattoo and Greg Hewett’s The Eros Conspiracy. Robin Becker and Kate Lynn Hibbard were nominated for The Domain of Perfect Affection and Sleeping Upside Down, respectively.

Poets Jennifer Rose and Justin Chin won, respectively, for Lesbian and Gay Male poetry. Justin’s Gutted was nominated along with Jim Elledge’s A History of My Tattoo and Greg Hewett’s The Eros Conspiracy. Robin Becker and Kate Lynn Hibbard were nominated for The Domain of Perfect Affection and Sleeping Upside Down, respectively.

The truly remarkable renaissance man, Eric Bentley (at the left) was recognized for his lifetime (when he mentioned in passing that he was 90, the room gasped!) of writing and activism…critic, playwright, editor, translator of Brecht, chronicler of Oscar Wilde in the play, Lord Alfred’s Lover…Bentley’s comments, which we hope to be able to reproduce here or in the pages of White Crane, reminded everyone present that LGBT people are still the targets of religious fanatics. He spoke of the pivotal roles that "love and death" play in the arts and literature and cautioned that there was still plenty of both in store for LGBT people.

The truly remarkable renaissance man, Eric Bentley (at the left) was recognized for his lifetime (when he mentioned in passing that he was 90, the room gasped!) of writing and activism…critic, playwright, editor, translator of Brecht, chronicler of Oscar Wilde in the play, Lord Alfred’s Lover…Bentley’s comments, which we hope to be able to reproduce here or in the pages of White Crane, reminded everyone present that LGBT people are still the targets of religious fanatics. He spoke of the pivotal roles that "love and death" play in the arts and literature and cautioned that there was still plenty of both in store for LGBT people.  Finally, Andrew Holleran, recent author of Grief, and the fabled Dancer From the Dance, received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Finally, Andrew Holleran, recent author of Grief, and the fabled Dancer From the Dance, received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement.