Stephen Wayne Foster is almost a Native Floridian. Though born in Virginia in 1943, he moved with his family to Miami a year later and grew up in Miami Shores. Foster studied at Miami-Dade College and the University of Miami, where he received a Bachelor of Arts in English with a minor in History. Now retired, Foster lives in an apartment in Coral Gables that he first occupied in 1975, having lived through almost a century of South Florida gay history and culture.

When Foster was 17-years old and in high school, he discovered gay history. "I came across Sir Richard Francis Burton's [in picture, left] translation of the Arabian Nights from 1880 which included a very long article about the history of homosexuality. But for many years I didn't know where else to look for it [gay history]. In 1969 I went to Washington, D.C. I went to a newsstand and bought a copy of GAY, the Jack Nichols publication. I took the issue home with me and read an article by Dick Leitsch of New York Mattachine about gay history in which he said that nobody was writing about gay history and that there was a need for this. So I felt that if anybody was going to do it I should do it."

"At that time I was still a student at the University of Miami. So I took a notebook and a pen and I went into the student library and saw thousands of books before me and I didn't even know where to begin. But on the very first day I came across a book written a century ago called The History and Development of the Moral Ideas by Edward Westermarck. And this contained a long essay about gay history and anthropology and it formed the structure for all of my research after that."

"My mother died in 1970 and I moved away from home. And my father died in 1973. At some point I developed a habit of going down every Saturday to the University of Miami and spending the whole day at the Library doing research. I also went to the public libraries, to the medical library, the law library, every important library in Dade County and collected a vast amount of information. Eventually I gathered notes from at least 5,000 books."

Though Foster realized that he was gay when he was 13, he did not come out til 1969 when he first met other gay people and discovered Miami's "gay beach" on 21st Street and Collins Avenue. That was a time when the Miami Beach police ("real bastards" in Foster's opinion) used the laws as excuses to raid gay bars and make gay folks' lives miserable in so many ways. For this and other reasons, it took time for Miami gays to get organized. When activist Frank Arango came down from New York in 1972, Foster remembers, he Awas dismayed to find that there was no political base so he had to create one. Word got out and we met at the house of Barry Spawn," another local activist. Out of this meeting was born the Gay Activists Alliance of Miami (GAA-Miami).

According to Foster, GAA-Miami met at Spawn's home for a while before moving to the Center for Dialog, an activist group connected with Miami's St. John Lutheran Church that Foster dubbed "the center for all radical activity in Miami." (Miami's MCC also met at that Church.) Its founders, all white men (except Arango), formed the Executive Committee: "The president of the group was Bob Barry. The Vice President was Barry Spawn, I was the Treasurer and Bob Basker [best remembered for his later work with the Dade County Coalition for Human Rights] was Secretary. Frank Arango helped us out but I don't think he had a position. And the reason that they gave me the position of Treasurer is because I had to take the money of the organization and put it in my own private banking account under my own name since I was the only person they trusted with the money," he says.

One of Foster's achievements during his GAA-Miami days was the creation of South Florida's first LGBT

library. Foster approached the Rev. Don Olson, pastor of St. John's Lutheran Church, and "asked him if I could use the room on the second floor. Olson gave me the go-ahead. He put some shelving into a small room on the second floor of the Center for Dialog and I took my private collection of books and publications and put them there. But three weeks later he came to me and said that he was embarrassed if straight people might walk past the open door of the library and see that it contained gay material so he wanted me to keep the door shut. I felt very insulted by that and I took all the material and took it home. So the gay library was the first one that we had but it only lasted maybe three weeks." This was a year before Mark Silber founded the Stonewall Library.

In 1972 GAA-Miami filed a class action suit against Miami Beach that led to the overturn of that city's law against cross dressing. Foster contributed to this victory by providing GAA-Miami with incriminating information about the Miami Beach Police Department that he had collected. Later that year Foster and other GAA-Miami members joined other activists to protest both the Democratic and Republican conventions that were being held on Miami Beach. To accommodate all the protesters, the City of Miami Beach opened Flamingo Park and let the protesters camp there. "There was a special area off to one side in the Park that became the 'gay area,'" Foster adds, one that attracted its share of queer notables.

In 1972 GAA-Miami filed a class action suit against Miami Beach that led to the overturn of that city's law against cross dressing. Foster contributed to this victory by providing GAA-Miami with incriminating information about the Miami Beach Police Department that he had collected. Later that year Foster and other GAA-Miami members joined other activists to protest both the Democratic and Republican conventions that were being held on Miami Beach. To accommodate all the protesters, the City of Miami Beach opened Flamingo Park and let the protesters camp there. "There was a special area off to one side in the Park that became the 'gay area,'" Foster adds, one that attracted its share of queer notables.

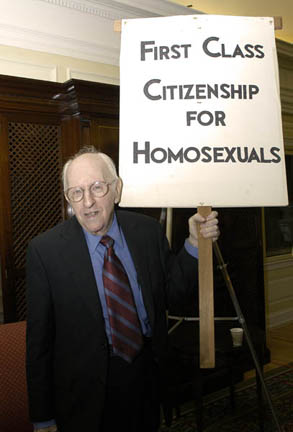

One of those notables who visited Flamingo Park was Dr. Frank Kameny, whom Foster had met previously through their mutual friend Bob Basker. Dr. Kameny came to Miami for the conventions and Foster joined

him on a tour of the Park. One of the colorful creatures Kameny encountered in the gay section was "a somewhat overweight gay teenage boy known as Corky. He was in the gay area of Flamingo Park and he was persuaded to put on some sort of outrageous costume, complete with feathers. And he paraded up and down and some tourists stopped by to take pictures of him. And all of a sudden Kameny showed up and said, 'Corky! What are you doing? You are giving homosexuality a bad name! Take off those feathers!' I thought that was priceless," he laughs.

Unfortunately, GAA-Miami did not long survive the 1972 conventions. As Foster recalls, "the thing that killed it was simply that people were showing up during the conventions and then when the conventions went away and the antiwar demonstrators went away and the whole thing died down and returned to normal then the people lost interest." Foster himself lost interest when he "got into an argument with a member of the Executive Committee and resigned. And I sent them their money that was in my account. And they took the money and sent out an emergency letter to all 250 people who were on their mailing list, asking them to show up for an emergency meeting so they can get the organization going again. And they [the EC] showed up at the meeting place and waited two hours and nobody showed up. Nobody!" By the end of 1973, GAA-Miami was history.

After Foster left GAA-Miami, he "was involved in the creation of a gay student group at the University of Miami," which was also short-lived. Unfortunately, in 1974 Foster developed a severe case of agoraphobia, which discouraged his participation in Miami's growing LGBT movement though of course he kept up with new developments. (Foster has since recovered from his agoraphobia.)

Foster's withdrawal from the political arena allowed him to return to his first love, gay history. By the late seventies, Foster had become a major contributor to the growing field of gay studies. Foster's "introduction as a gay historian" was an essay on Sir Richard Francis Burton. ["The Annotated Burton"] that appeared in the anthology The Gay Academic, edited by Louie Crew [ETC, 1978]. "At the same time I was helping Jonathan Ned Katz write his book Gay American History [Crowell, 1976]. I gave him very significant help." In his groundbreaking book, Katz gave credit to "Foster's inspired research assistance [which] led to the discovery of numbers of important documents." Through the years, Foster "helped many other gay scholars write their books. And my name is mentioned in at least thirty books, usually in the form of footnotes saying 'I wish to thank Stephen Foster for his help.' " Foster also contributed original essays and translations to the pioneer gay journal "Gay Sunshine."

Though Foster was never a member of the Gay Academic Union, he contributed to the GAU's periodical "The Cabirion," aka "Gay Books Bulletin" [1979-85]. Through the efforts of "Cabirion" editor Wayne Dynes, Foster contributed an article on gay communities for The Encyclopedia of Southern Culture [Edited by Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris, UNC, 1990]. Foster followed that achievement by writing, for the Dynes-edited Encyclopedia of Homosexuality [Garland, 1990], articles on such diverse topics as Adelswärd Fersen, Afghanistan, Sir Richard Burton, Ralph Chubb, Charles Fourier, Henry B. Fuller, Robert de Montesquieu, Pirates, Poetry, Travel and Exploration, Edward Perry Warren and Oscar Wilde. Though some of the other contributors to the Encyclopedia of Homosexuality used pseudonyms (which caused a bit of a controversy at that time), Foster is quick to assert that in this case, as "in all of my writing, I used my real name." All in all, Stephen Wayne Foster should be credited for some of the most notable contributions to our culture.

This is the second of a series of articles about the history of South Florida’s LGBT community. The first one was a personal account of the Miami bar scene in 1974. I invite other veterans of South Florida's LGBT community in the 1970s and 1980s to share their experiences with us. You may reach me at jessemonteagudo@aol.com.